The authors are careful, unlike many, not to serve up a naïve universal portrait of feminism. She Animates reveals that feminism in Soviet Russia was different from its counterpart in “the West” (granted, it does seem a bit odd that the people writing this are both from “the West”). In “the West,” Leigh and Mjolsness argue, feminism was about rejecting difference, whereas in Soviet Russia, it was about emphasizing and celebrating difference:

In the end, as the authors write on the opening page, wouldn’t it be nice if we could stop with all this? If we could reach a point — and I’d argue that independent animation comes close — where “female directors are so prevalent that their gender is no longer an issue”?

Saddled with the triple burden — motherhood, housework, and career — Soviet women wanted to display their differences from men. Both in live-action cinema and in animated film, Soviet women had a desire not for a Western style equality, but rather for an acknowledgement of their differences.

Soviet Union feminists fought for the right to be feminine, to have the freedom to wear mini skirts, make-up, and Go-Go boots.

Within each phase, the authors explore how these animators negotiated a changing sociopolitical framework (Stalin’s repression, Khrushchev’s thaw, Brezhnev’s stagnation, the ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union) and shifting ideas of women’s role in society.

She Animates also serves as a handy introduction to Russian/Soviet animation history in general. From the early independent collectives of the 1920s (when, yes, animation had an adult audience), the narrative moves on to the rise of the Disney-influenced state studio Soyuzmultfilm (and its emphasis on propaganda and kids’ films), and the eventual reemergence of defiantly individual artists like Nina Shorina (The Door, 1986).

Starting in the post-revolutionary period of the 1920s, where the first wave of women animators (Valentina and Zinaida Brumberg, Olga Khodataeva, and Mariia Benderskaia) began, Leigh and Mjolness take us on a decade-by-decade journey through the volatile and rapidly shifting political, social, and cultural landscape of Soviet Russia.

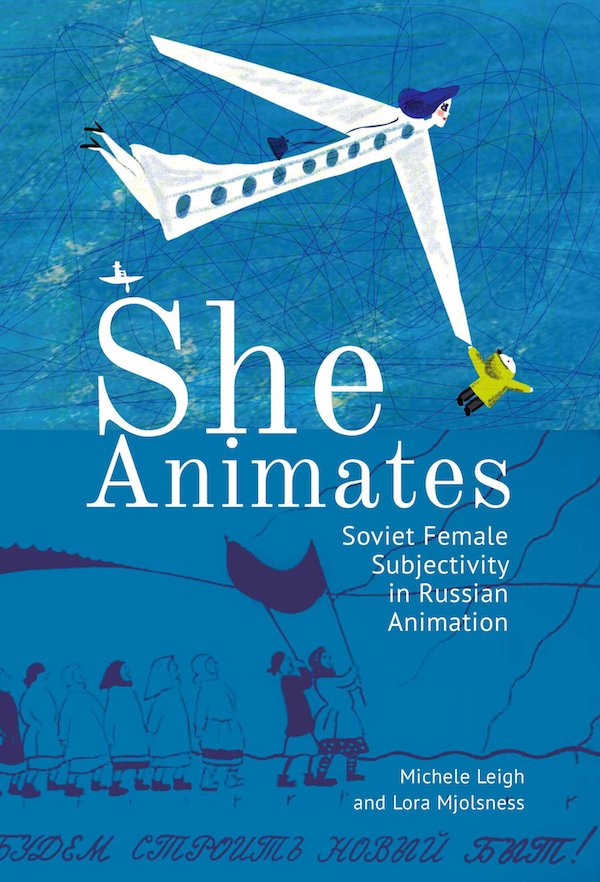

She Animates: Soviet Female Subjectivity in Russian Animation by Michele Leigh and Lora Mjolsness. Academic Studies Press.

Another distinction: while feminism in Soviet Russia and the West were similar in their desire to use fashion as a sort of weapon, Soviet feminists didn’t seek to erase gender boundaries: