Simone Giampaolo: I stumbled onto Severn Cullis-Suzuki’s speech around four years ago (before the climate strike movement and Greta Thunberg became a global phenomenon) and immediately felt the urge to adapt it into an animated film. I got in touch with Severn, who was very interested, and got her official permission and blessing to use her speech. After that, I pitched the idea to Amka Films, a production company based in the Italian part of Switzerland, which is where I’m from. Amka’s producers, Gabriella de Gara Bucciarelli and Tiziana Soudani (who unfortunately passed away in 2020), were enthusiastic about the proposal, and agreed to help raise funding for the project.

In 1992, 12-year-old Severn Cullis-Suzuki gave a speech at the UN Summit in Rio de Janeiro, in which she talked about environmental issues from a young person’s perspective. The video became a viral hit, and Cullis-Suzuki became known as “the girl who silenced the world for five minutes.” 30 years later, we continue to face life-threatening environmental crises, notably climate change; and, 30 years later, not nearly enough is being done to preserve our species and our planet.

SG: We started gathering funding for the film at the beginning of 2019. The actual production began in the second half of that year and lasted more or less one year in total. The line producer, Ursula Ulmi, and I planned to make the entire production remotely, even before the appearance of COVID. Since the teams were scattered in different cities – and countries, the decision to use chat, video calls, and emails to communicate seemed the most practical and logical.

The production pipeline was arguably the easiest part of the project, since almost every artist was in charge of designing, animating and completing her/his own segment without sharing files with other departments. There were a few exceptions, though, where multiple artists had to collaborate and work together in order to achieve a certain transition and/or a peculiar visual style).

It was a project close to my heart not only because of the theme, but also because since I first started working in animation, I had always dreamed of crafting an ambitious film that could combine every animation technique in existence. When pre-production began on Only a Child in 2019, I immediately saw an opportunity to make this finally happen.

AWN: Ideally, what do you want audiences to take away from the film?

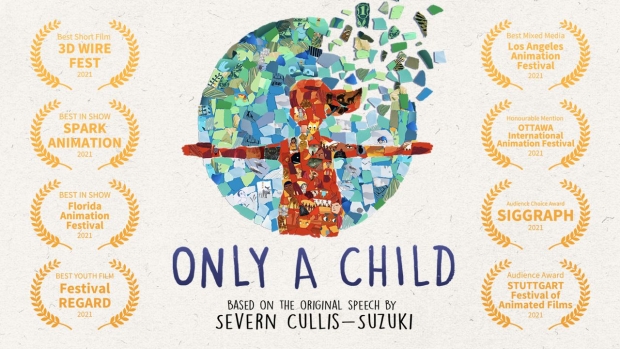

Only a Child has been selected by over 100 festivals worldwide, winning a number of prestigious awards, and has been shortlisted for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film.

In the compelling Only a Child, more than 20 animation directors under the artistic supervision of director Simone Giampaolo revisit this historic speech, giving shape and color to the original words spoken in 1992. Each artist involved in the short’s creation used their own unique style and technique to bring a segment of Cullis-Suzuki’s speech to life: stop-motion, CGI, traditional 2D, cutouts, sand animation, paint on glass, and more.

AWN: How were the directors selected?

But first, take a moment to watch the film, available until February 8 on the KIS KIS Keep It Short! YouTube channel:

In an interview conducted via email, Giampaolo talked about the origin, funding, and production of the film.

SG: Managing everyone’s time and setting individual calls for feedback sessions – alongside my daily job in London – was the most difficult part of the project. For many months, I found myself having meetings for Only a Child at each and every lunch break, not mentioning during evenings and weekends. Luckily for me, Ursula was a great line producer, who was invaluable during this whole process.

The contributors included Monica Santana & Julian Amacker (Walkingframes), Marjolaine Perreten, Andrea Schneider, Emilien Davaud, Barbara Brunner (Brunner & Meyer), Nino Christen, Patrick Graf, Imgart Walthert, Oswald Iten, Philip Hofmänner, Yves Gutjahr & Claudia Röthlin (Tiny Giant), Michaela Müller, Justine Klaiber (Team Tumult), Nina Christen (Team Tumult), Cyril Gfeller, Roman Kaelin, César Díaz Meléndez, Eisprung Studio, and Stéphan Nappez.

SG: The film received funding from Swiss TV and the Swiss government, which meant that most of the team had to be Swiss or located in Switzerland, even though we had several exceptions. Selecting the team among so many talented independent artists was a real challenge and took a long time. In the end, I was very happy with the diverse group that we managed to assemble. Interacting with artists who use so many different animation techniques has been an incredible learning opportunity for me.

Otherwise, the biggest challenge was splitting the budget into 20 different sub-budgets, one for each segment of the film, keeping in mind the different pipelines and workflows that each animation technique requires. Working with so many different independent artists forced me to become extremely flexible and open to experimentation. As director, my main challenge was to provide each animator with as much artistic freedom as possible, while maintaining a common thread throughout the visual narrative.

AWN: What were the biggest challenges in making the film?

[embedded content]

In assembling Only a Child’s “dream team,” I tried my best to give equal weight and importance to each animation technique. Artists were selected for their skills, of course, but also for their unique visual style and their individual abilities. It goes without saying that finding a digital 2D animator was way simpler than coming up with a sand or paint-on-glass artist!

AWN: What was the production process like?

SG: I’d like it if Only a Child caused audiences to reflect on the lack of environmental action taken by the nations’ governments. It’s been 30 years since Severn gave her speech to the UN Summit. Could we have done more? Of course, but pointing a finger now won’t help us to solve the crises we face. Only acting as soon as possible will.

AWN: What was the genesis of the project and how did you become involved?

Jon Hofferman is a freelance writer and editor based in Los Angeles. He is also the creator of the Classical Composers Poster, an educational and decorative music timeline chart that makes a wonderful gift.