AWN: Once you were working with Peele on the story side, how long did it take to work out the guts of the film?

When Coraline’s pulled out of the water and transforms, the surface of the water’s all hand-animated plastic, which is really crude, but it’s also beautiful. So it was a conscious effort to try to hold onto the things that prove it’s hand manipulated – that people actually breathed life into these puppets and they had to walk them across a chasm, with no assistance, no computers to refine the timing, but in an actual performance. So that’s why you do stop-motion. It can’t be perfect. And why does it have to be?

And then, finally, we get to shooting digitally. The cameras can be much, much smaller. The rigs don’t have to be as robust. We can fly them around and, now, instead of hanging a character from spider wiring and a whole complex rig to make it jump and you’re trying to animate as it’s going, we can have a metal rig that’s attached and then shoot a clean pass and paint that out. So you could have characters of bigger sizes. They didn’t have to support their weight. You could fly them more easily and you could capture the whole performance and play it back. You didn’t have to wait for the lab.

HS: Generally not that much because it usually comes later. In the case of Kat and her look, certainly it was heavily influenced by Afropunk, which is a modern movement that goes back to the first wave of punk music, Black punk in particular. Bands like Bad Brains and Fishbone and Pure Hell. But for Jordan and me, it was initially just a cool look for Kat. I mean, if you look up Afropunk and you look at the styles, it’s phenomenal. It’s a beautiful, huge range of looks. So it started as a look thing. But then we did have to find the music. How is Kat going to walk when she’s transformed her school uniform into this punk outfit? How does she move? So that’s when the song came into play. And then, subsequently, in other scenes the song became the guideline for the rhythm of the whole thing, like when Wendell and Wild are raising the dead and doing all those old-guard guys. That becomes the rhythmic guide for all the movements.

We spoke with Selick about his and Peele’s collaboration, the place of stop-motion in the contemporary animation landscape, and the ways in which his tools and techniques have changed over the years.

HS: In the beginning, with The Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach, we shot on film. We had these old Mitchell movie cameras, which are meant for live-action. They were huge and heavy. On Nightmare, we wanted to bring in a lot of camera moves – swoops and other things – because that hadn’t really been done so much in stop-motion. So the rigs had to be really heavy-duty and huge. And it was quite a challenge to fly those cameras around. Because we’re shooting on film and we can’t see the results until later, we could only hope that it was going well. We almost always filmed some kind of a rehearsal to help fine-tune the movements, but it was still agonizing not knowing how it was until the film got back from the lab.

Henry Selick: One of the first things I discovered in meeting Jordan, which proved to be really helpful and sort of a bedrock truth to our relationship, is that he loves stop-motion animation, and he knows all about it. In fact, the logo for his company Monkey Paw is stop-motion animation. So right from the start, that gave me a leg up. It was like, “This is incredible. He’s coming into this with this knowledge, and a lot of love and appreciation for what I do.”

So, honestly, everything changed for our movie, because after that everyone wanted to be in the Key & Peele business. We found a really good home, though, because Netflix was the only studio that pretty much guaranteed they would make the movie. They didn’t say, “Oh, we love it, let’s develop it and see what happens.” They said, “Our attitude is if we like you, and we like the project, we are going to make this film.” And they stuck with us. I mean, we went through hell with the pandemic, and we had some other big challenges that added costs and a lot of time. Ultimately, to make the movie took four years. It’s the most I’ve spent.

HS: Yeah. I’m a patient man and I’m relentless.

AWN: You speak of the imperfections in stop-motion that give it its unique quality. How does that technique speak to your creativity and your goals as a filmmaker?

AWN: What was it like working with Jordan Peele, and how did the production come together?

Featuring the distinctive and highly expressive character designs of renowned illustrator Pablo Lobata, Wendell & Wild is both a continuation of, and in some ways a departure from, Selick’s previous work, which also includes James and the Giant Peach (1996) and the Oscar-nominated and Annecy Grand Prize winner Coraline (2009). Selick credits Peele – who pushed for a different approach to the young protagonist originally envisioned by the director – whose ideas “triggered a wonderful creative rethink of the whole film.”

HS: Yeah. We shoot 24 separate frames, but we often mix in twos – so there’s 12 frames a second – if something’s moving more slowly. And it may stutter a slight amount, but I kind of like it. But, yeah, at the end of the day, it’s still a human being moving something. I mean, the level at which the best stop-motion animators can animate is astonishing to me. I couldn’t do it. They’re like brain surgeons. Their skill level is just amazing. They are literally performing through the puppet. And if they fuck up along the way, now it’s not a disaster.

Even in the first series of Star Wars films, there’s some stop-motion, where the animators were trying to make it as good as possible. But the end of that idea, I believe, came with Jurassic Park, when it was a decision between working with Phil Tippett doing amazing stop-motion dinosaurs, or this brand new CG – and CG won. And they were spectacular, those first CG dinosaurs in a film. And it kind of said, CG can do perfect, CG can do smooth, and it’s only gotten better since then. And that applies to the computer-animated features of Pixar too.

HS: There was a time in history, before CG, when that’s how monsters were done – the good monsters, the Ray Harryhausen stuff. When you look at them now, they look pretty crude. They really bump and the fur on them might all boil and swim around, but they worked for their time. People believed in them. One of the first movies I saw was The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad. My mother took me because she liked a little bit of scariness, but I had nightmares about the Cyclops in that.

But the most important thing it did was give us a second chance if something unforeseen happened. These puppets are tensioned, metal armatures, and some of them could be quite big, like Oogie Boogie in Nightmare. So you have to tighten these things down enormously for them to hold their weight. We didn’t attach rigs to everything back then. You had to use spider wire to fly something. But, with these digital frame grabs, if something broke and the puppet fell over, or something got knocked and jarred, or you’re doing a shot that takes two weeks and during the night the set kind of shifted and things don’t line up, we now could send the puppet to the puppet hospital, get it repaired, bring it back, click between those frames and line it up again, and keep going. I know it sounds like a very small thing, but getting those digital frame grabbers was huge.

AWN: Last question: I’m always surprised how many animators are also musicians. You’ve spoken a lot about music being an integral part of the film. How much does the music, or even specific pieces, influence the design and the animation itself?

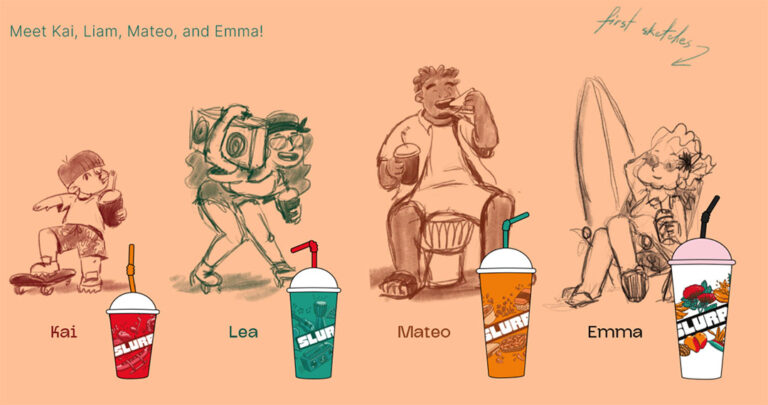

The second thing, which took a while, was I really wanted the demons who were voiced by Key and Peele to be caricatures of them. And they were both a little hesitant because caricatures can be clunky or weird. There are examples in other animated films that didn’t really work so well. I’d done a few sketches, but I always go to someone better than me for the finals. So I reached out to this artist, Pablo Lobato, and told him about the project, and he started doing sketches right away. His work is naturally very graphic, almost Picasso-esque, but very readable. I mean, he just boils down a person’s face into these geometric forms and captures their essence. And Key and Peele got on board pretty soon after he had put some of his work to color.

The only problem was that people would naval gaze too much. They’d have 10 frames of animation, not even half a second, and they’d watch it over and over and over again. And I’d say, “No, you’ve got to put your blinders on. It’s great that you can play it back, but the performance is a one-way thing and you’ve got to keep doing it. And if there’s a problem or a mistake, we can do a cutback, or I’ll just have you restart back here.” But that became quite a challenge, just to get the animators to keep animating. Because if you look at it over and over again, it’s going to fall apart. You’re only going to see the flaws.

So, for me, there’s always the question of why bother doing stop-motion at all. I mean, the fact that I love making it and I love the results means only so much. In Coraline, especially with facial animation, we were able to bring it up to a level that it had never achieved before. But I feel like, from that moment on, stop-motion could look so perfect that it might as well be CG. So, the point for me is to really embrace the fact it’s stop-motion – to show off the fact that the faces are made from separate pieces, like they were in Coraline. Back then, they were digitally cleaned up, but now I say, let’s leave that in. Let’s leave in mistakes. Not the worst mistakes, but let’s leave in the minor flaws.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.

The first breakthrough that people came up with was a digital screen grab. That meant we could put a video tap on these movie cameras and could grab only two frames, meaning every frame you shoot, it gave you the ability to go click, click through the previous two frames up to live. Click, click, live. Click, click, live. And it maybe gave you a better sense of the flow.

But translating that into puppets and characters was quite challenging. The very first bit we did of Wendell & Wild was the two demons when we first meet them, and I literally went with Pablo’s designs and did sort of a relief – almost flat faces, while the bodies are fully dimensional. And we managed to get that to work, but we also felt like it’s an extreme look and it might be tiresome if all the characters had that same kind of trick for the whole film. And so we worked with Pablo to see whether his designs could translate to more dimensional characters. Can we hold onto his strengths, even with dimensional heads that turn? And we found a way to do that. He was very gifted in terms of adapting his designs to be a little more three-dimensional, but still totally his.

A tale about scheming demon brothers Wendell (Keegan-Michael Key) and Wild (Jordan Peele, who also co-wrote and co-produced), who enlist the aid of 13-year-old Kat Elliot (Lyric Ross) — a tough teen with an affinity for Afropunk — to summon them to the Land of the Living. However, what Kat demands in return leads to a bizarre comedic adventure like no other, in which the laws of life and death are sorely tried.

AWN: How was it different doing the stop-motion on Wendell & Wild, compared to your other films over the decades?

HS: It took a while because, when I first met with him in 2015, he was still doing Key & Peele, which was a very involved show with long hours. It was only after the show had its last season that we got to more serious work. The total amount of time was probably two years. But in that two years, he also made Get Out. And so he went off and did his film and then he comes back out and the film’s getting ready for release and he’s kind of terrified. “What if it’s a bomb? We got to take Wendell & Wild out this week, we got to set it up this week.” I said, “No, you can’t worry about that. You just got to put all your efforts into promoting Get Out.” And then it comes out and it’s a life changer.

AWN: So a lot of production techniques have evolved over the years. Yet, as much as things have changed, you’re still manipulating it a frame at a time. You’re still touching every aspect of it for every second it’s on the screen.

AWN: Just for the production, not pre-production.

It has demons. It has ghosts and zombies. It is, as director Henry Selick says, “a perfect film for Halloween.” It is also Selick’s latest tour de force of stop-motion animation, a specialized technique in which, since his rise to fame with 1993’s Oscar-nominated and Annie Award-winning The Nightmare Before Christmas, he has become one of the most accomplished contemporary practitioners.