People who haven’t gone through this kind of tragedy say, “I can never imagine losing a child.” This film is not even close to what the reality is, but it’s a way to begin those conversations.

Govier: We were very sensitive to that. We reached out to the organization Everytown for Gun Safety and they became a friend of the film. We sent them the script and an early animatic to get their feedback, and make sure we were honoring the survivors and honoring these stories. They couldn’t be more impressed with what we did. They wanted to be on our side and boost the message of the film.

McCormack: It was surreal. My niece texted me a couple of days after the movie came out on Netflix and said, “Uncle Will, your movie’s trending on Tiktok?” And I was like, ‘I don’t even know what that means.” I don’t speak Tiktok. I downloaded the app and there were people all over the world, mainly kids, filming themselves before, during, and after the movie.

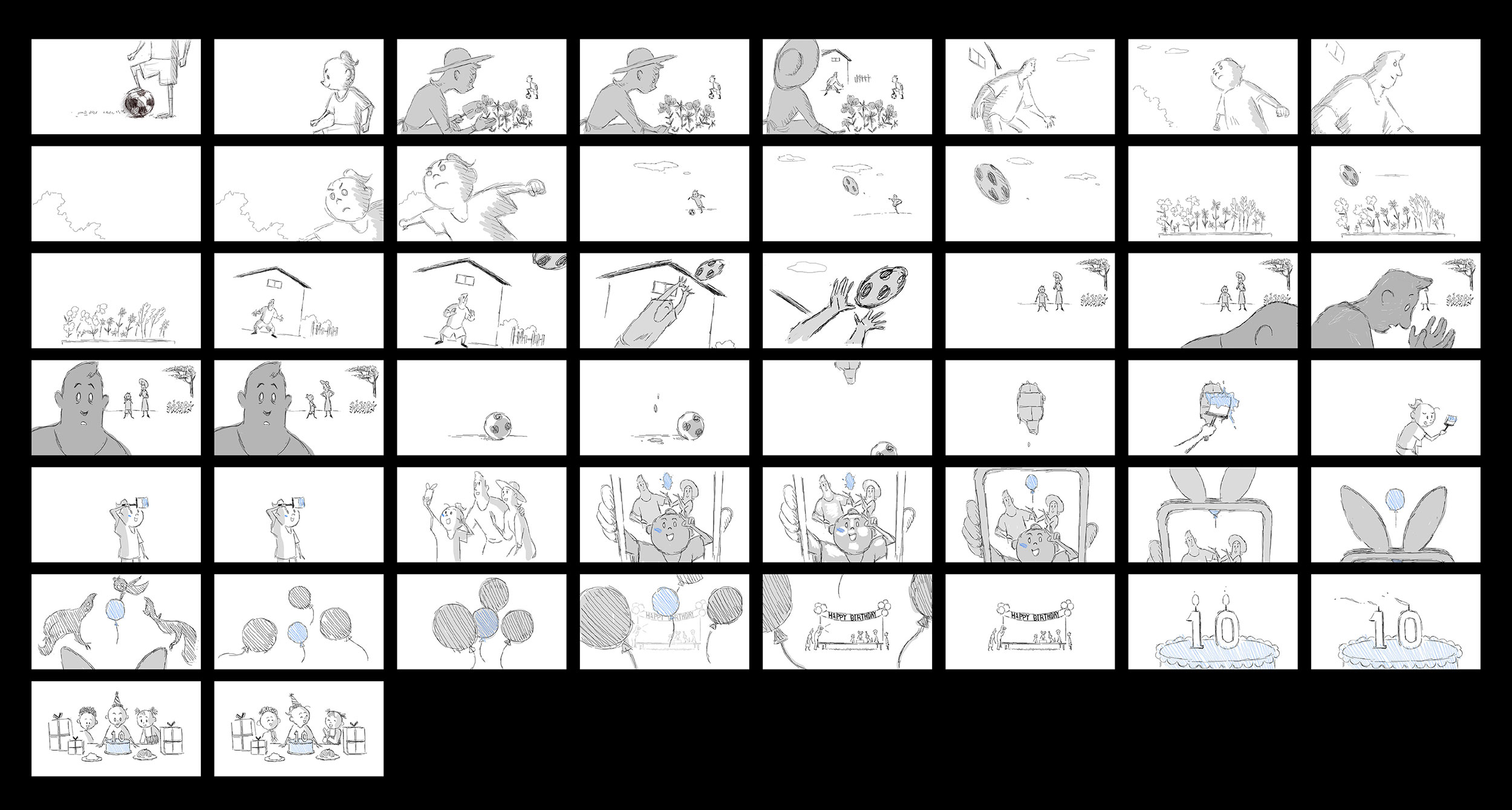

The writing process took a long time, about a year. Everyone gets to the story in different ways. Some people start with images and then drive to story. Some people start with words and drive to story. We took about a year to write the full script, which was only about 12 pages, and we just kept distilling it. We also kept focusing on rewriting the transitions that you see in the film. We explored all of those through the written word.

Michael Govier: From the very beginning it was always going to be an animated film. We just thought a live-action version of this would be way too intense. We thought animation was the perfect gateway to have these deep conversations about loss and grief.

Govier’s and McCormack’s answers were edited for brevity. “If Anything Happens I Love You” can be watched on Netflix.

That one image of the shadows told a beautiful story. It really worked here because in that level of grief, you’re sort of caught between two different worlds and their daughter functions as the engine for the story. She can reunite their souls back with their bodies, so that they are able to face one another as they talk through the night.

Welcome to our series of interviews with the directors of this year’s Oscar-nominated animated shorts. Every day this week, we’ll be speaking with one of the five nominees in the category. Our guests today are Michael Govier and Will McCormack, directors of If Anything Happens I Love You.

We got also in touch with another group, Moms Demand Action, and different survivors. We talked to them directly and they shared their stories with us. They were grateful to see this kind of film, because they said people constantly ask them what it’s like having this experience and now they say, “You can just watch this to understand those lonely moments of grief.”

Tell me about the very deliberate use of color in the short. The palette is predominately muted for most of the story, but eventually brighter tones make their way in purposefully.

When the color starts to come back, the edges of the frame are still gray and washed out, because it’s still seen through the current sorrow they feel. But hope and love start to come in as the parents reconnect. That’s when you start to see more ambers and soft yellows, warmer tones that fill out the second half to the end of the film.

Almost immediately after being released on Netflix, the film had an impact on social media — particularly on Tiktok, where it went viral with people challenging each other to watch it without crying. How unexpected and rewarding was this for you?

It was exciting animating and designing the shadows because of the freedom of how they move, similar to smoke. They’re not exactly tethered to the human body. If you see the first shot of the film, the bodies are flipped from their actual shadow souls. From the get-go, we’re trying to tell the audience that they do have freedom and they can move about.

Will McCormack: We thought we could do more with less. We wanted total parsimony and minimalism for a couple reasons. We were trying to capture the sort of barrenness and loneliness of what grief can feel like. We had a cardinal rule that anything that didn’t need to be in frame we would remove, because we wanted to hang a lantern on the simple and just the unvarnished raw emotionality of the scene. When there’s grief that acute, you just want to zero in on the emotion. That’s why I go to movies.

Now, with the Academy’s recognition and plenty of other accolades (including an Annie nomination for best editing in tv/media) to their names, Govier and McCormack have found their preferred medium in animation: they are already working on another animated short and an animated feature together. Cartoon Brew chatted with the pair about key aspects of their animation breakout.

Cartoon Brew: Given that you were pretty new to animation, why did you feel it was the right medium to approach this delicate social issue?

McCormack: That was Michael’s original concept. He talked about a Jungian image of the shadow souls that were disconnected from their human bodies or hosts because they were in too much agony. I’ve been through some loss, and I know what it’s like to feel disembodied from your soul and have that disconnect.

With gun violence a horrific and ever-present source of tragedy in the U.S., the creative partners chose it as their vehicle to deal with those complex emotions, specifically from the point of view of two parents who have lost a child. That was the genesis of their hand-drawn short film If Anything Happens I Love You, which is distributed by Netflix. The moving, expressionist, silent tale follows a couple grappling with their daughter’s death in a school shooting.

In true L.A. form, Govier and McCormack met in an acting class a few years ago. Becoming fast friends, the duo would often talk about the stories and themes they hoped to wrestle with in their work. They both were interested in originating projects as writers and directors. At that point in their lives, they were compelled to write about loss and grief.

Govier: We knew it was always going to be 2d. We wanted the story to dictate the style, not the style to dictate story.

The concept of the shadows as interlocutors able to express the sadness that these parents can’t verbalize adds an extra layer of thematic depth to the piece. Why did you feel this element work for this film?

Once you decided that animation would be the vehicle, why did you gravitate to the hand-drawn aesthetic we see in the film? Was it perhaps that it allows for more stylistic liberty or narrative abstraction?

Govier: A hundred percent because you are still working with actors — they’re animated actors, but all of those human emotions and reactions have to be there. We talked through the emotional state of every moment, how they’re feeling when they enter the room, or how the father feels when he comes into the room and sees the mom hold the shirt up. Dad smiles and then that smile kind of fades.

Final Oscar voting takes place on April 15–20. The winners will be announced at the ceremony on April 25.

That’s a moment we filmed each other acting out to get emotional nuance, as opposed to just one flat thing. You’re happy to see your daughter’s shirt because you love your daughter, but you’re also sad because she’s no longer here. All of these emotions are flooding in at once. This is where our background in acting helped us communicate to Youngran and the other animators how to build out these wonderful moments.

Govier and McCormack had never directed an animated project (although McCormack has a story credit on Toy Story 4). They first enlisted seasoned producer Maryann Garger (The Lego Ninjago Movie) to turn their screenplay into a 2d reality.

To set things in motion, Govier, McCormack, and Garger self-funded the movie’s animatic, then screened it to attract investors. The team received fiscal sponsorship from Film Independent, and Gary Gilbert of Gilbert Films later supported them through Film Independent’s tax-deductible financing opportunity. Netflix came onboard after completion, once the short had received endorsements from A-list talent such as Rashida Jones (who is also McCormack’s long-time collaborator) and Laura Dern, who executive-produced.

Both of you have had careers in acting prior to this project. How do you believe that skillset was useful here, even though you were not working with onscreen or even voice actors?

Moreover, it seemed to work well in the memory section of the film. When you see the memory-scape of the film, that’s how implicit memory works. When you talk about the past, you don’t remember what was in the room, but you do remember how you felt. It was an intimidating style to commit to because it’s a movie without any dialogue, but once we committed to it, it started to pay off.

Since you were dealing with gun violence and its consequences, what sort of research or outreach did you do in order to portray this unique emotional pain as truthfully as possible onscreen?

Govier: We wanted earth tones, grays, blacks, and whites for the front half of the film. Then as you go into memory, you start to see color coming back. But it’s not full Technicolor because it’s still filtered through the present-day lens of grief. The parents are still sitting on the bed in that moment, having this conversation and remembering the wonderful ten years that they had with their daughter.

Later, Maija Burnett, the director of the character animation program at Calarts, helped them recruit artists with the right sensibilities to get across the pathos of the concept. One of them was Youngran Nho, who became the film’s animation director. Intending to use this film as a launching pad for emerging talent in animation, the filmmakers assembled an all-women animation team.