Dunka (Olivia Coleman), Barney’s grandma, knits Ron a woolen hat, which Denis notes, “became very humanizing,” adding, “He was not a robot anymore. We have the little pompom on top of it which became an emotional underscore. That was done in CFX unless animation had to do some specific with it and we just did a secondary motion. The hat was a nice visual contrast with the hard shell of Ron’s body.”

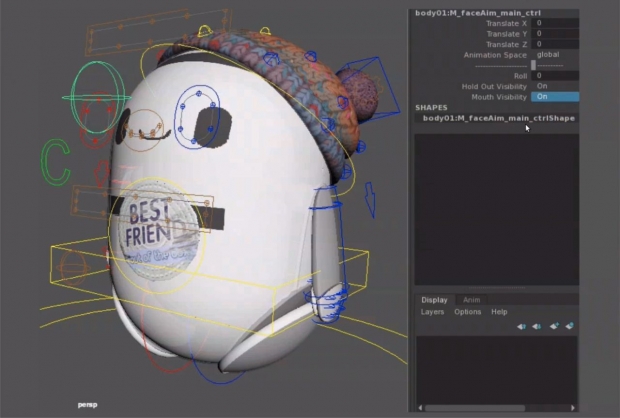

The film’s animation style was established early on in the scene where teenage Barney (Jack Dylan Grazer) discovers that his B*Bot named Ron (Zach Galifianakis) is defective. “For me, that’s still one of the best sequences because we could spend enough time to find and figure out the characters,” Sharma says. “I took care of Barney and Steven Meyer looked after Ron. In real life, we are friends, which paid off well because we could figure out the timing of these characters quite nicely.” Animation was done in Maya. “Our main concentration was on pipeline and how the different departments would talk to each other and integrate. We didn’t have enough time and resources at that moment to explore any software other than Maya. Maya is universal. We knew what we were doing, and it was easier to find things.”

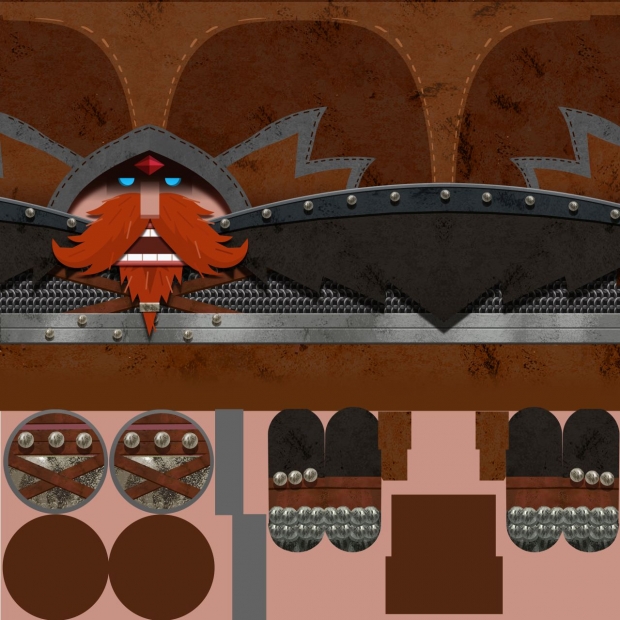

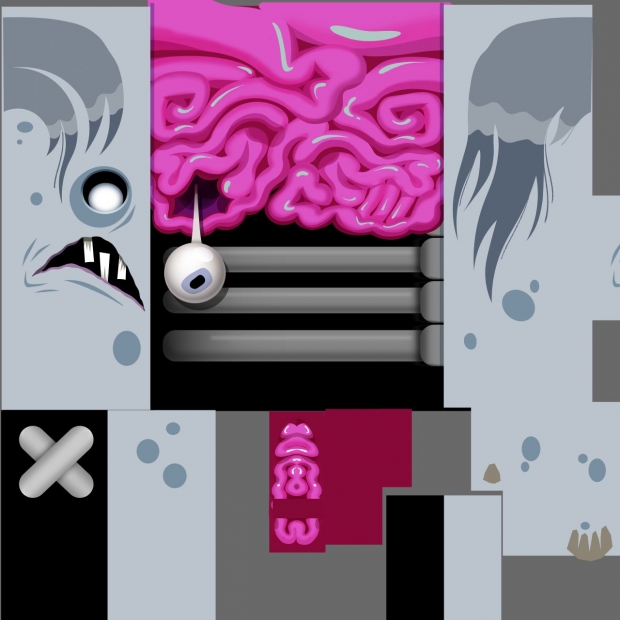

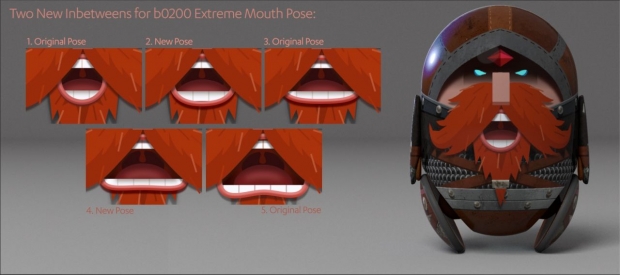

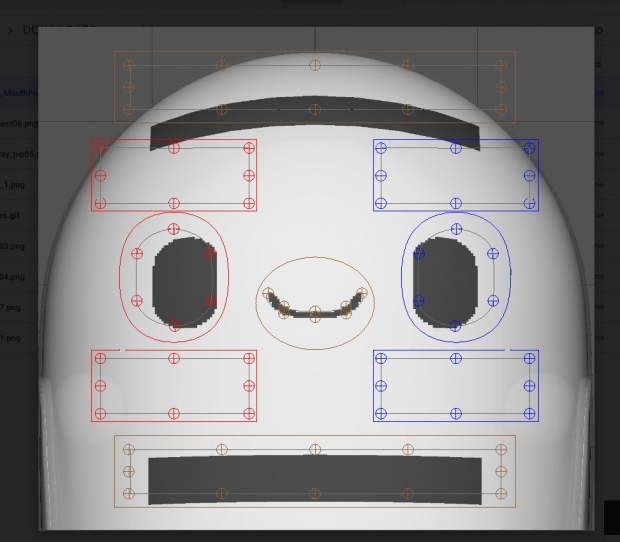

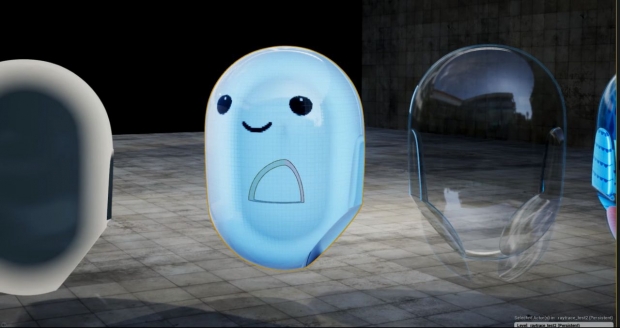

Integrating the motion graphics skins onto the B*Bots was a major task. “Ron and the B*Bots have a body, two arms and hands, and wheels,” observes Denis. “You generically rig for that, but the rest of the acting comes from the [B*Bots] screen, which are images. We started with Ron because he is a principal character, and he pixelates based on his emotion We had to give the control of those faces and images to the animators. Rigging drove the different expressions. The pixilation was another level on top so it could be controlled. The other B*Bots had a multitude of skins that were much more elaborate than Ron’s because they have a specific design. For the crowds we had automated animated B*Bots. We could put them in, so they looked animated and the ones that were further away we kept static and changed their color.”

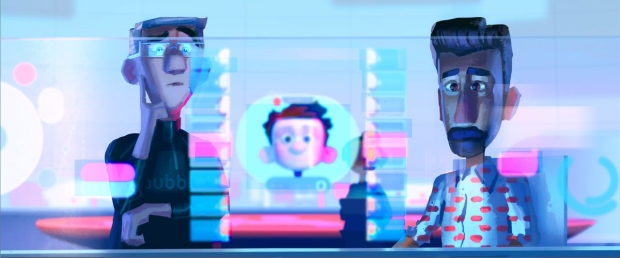

According to director Jean-Philippe Vine, “One of the myriad challenges we had, along with a pandemic, was figuring out how to establish a feature production with an ambitious new start-up (Locksmith) and a new Animation Division at DNEG. We wanted to deliver a film that matched the scope and beauty of films we’d worked on at the established studios but had to build the track as we went. This meant really holding hands in the storytelling of our film, it meant world class animators, and beautiful imagery and effects delivered by Philippe Denis and his crew. We worked extremely closely with our Animation Supervisors such as Kapil Sharma, who was responsible for Barney with his team – to reach performances with soul and comic charm. I also have to give a nod to DNEG’s amazing production and support teams. They got us through, and we’re delighted with the end result.”

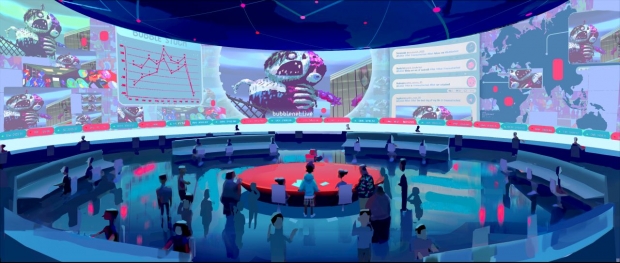

The high-tech Bubble headquarters was a challenging environment build. The pipeline had to be modified to handle the motion graphics; all the motion graphics were integrated into the database because they were being used by everybody, including surfacing and lighting.

The approach towards generic characters led to the adoption of a Universal Scene Description (USD) workflow. “That offered us an elegant way to make choices along the way,” notes Denis. “DNEG had its own asset package, but USD gave us a bunch of controls that we wanted to have. USD helped to give us choices and rules to establish all of those different generics. It was a big shift and was something that we developed for the show.”

Trevor Hogg is a freelance video editor and writer best known for composing in-depth filmmaker and movie profiles for VFX Voice, Animation Magazine, and British Cinematographer.

Simulations were developed to support the animation. “We needed to learn about the character and establish how much simulation you’re going to have on the clothes,” Denis says. “Is it to be pushed and stretched or is it to be more naturalistic? It’s a discussion that you want to have with the director. You also get the information from the animation. If it’s a natural animation, then the clothes should be natural.” One character, the school bully Rich Belcher (Ricardo Hurtado), wears a puffy jacket over his skinny body, which Denis says means “you run and constrain the simulation. The rig of the clothes is not elaborate so in CFX we try to get some key poses and between those key poses we run the simulation so that the jacket works in a more naturalistic way.”

Animation director Eric Leighton led the production in collaboration with supervisors Steven Meyer, Seamus Malone, Kapil Sharma – who has since been promoted to animation director at the studio – and Philippe Denis.

“Another important distinction from live-action [VFX animation] is that voice acting drives animation,” Sharma continues. “That’s how you imagine what the puppet should be doing based on what emotion you’re getting from the voice. Ron was a bit different because his voice is monotone.” A group of six animators became experts in animating Ron and Barney together. “There is a difference between when the two of them are together and when they are alone doing their own things.”

The production benefited from the established DNEG VFX pipeline designed to handle multiple high-volume visual effects-shot shows and allows rigs to be shared between projects. “DNEG had done realistic faces before Ron’s Gone Wrong, so the rigs were heavy and designed to capture realism,” Sharma explains. “You have to be a trained visual effects animator to handle them because of the endless number of controls. The first thing that Steven and I wanted to do was to simplify the rigs so we could concentrate on making nice designs for each face. We also had a lot of new animators, so the rig simplification made it easier for us to manage them. There were two different rigs. I was dealing with the human characters while the other side had all the B*Bots. We wanted to have a system that was simple but flexible enough that you can push beyond the realism and still maintain a nice design language that is charming.”

Denis enjoyed his involvement in Locksmith Animation and DNEG Animation’s first animated feature production. “I could bring something to the table but also, I could learn because of the award-winning visual effects experience of DNEG,” he shares. “What was amazing is we brought together people from Animal Logic, Aardman, DreamWorks, Mikros, Pixar, and Sony Pictures Imageworks as well as those coming from visual effects. That created a synergy and a blank canvas. You don’t fully reinvent the wheel because there is some structure that works in visual effects and animation. But you also want to make things better because we can. That’s the way we approached our first project. We learned a lot about how we want to work in pre-production, production, and the art approval process. It was brainstorming with so many people with so many experiences. We all do the same things but approach them in slightly different ways. It was picking what we thought was the best and put it together. There are other projects going on now which have different looks, but we have that base to build upon.”

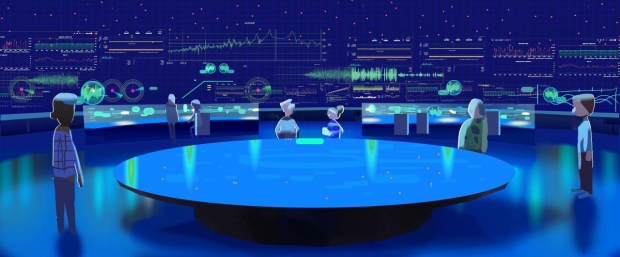

“The big thing was the motion graphics in the control room,” remarks Denis. “There were so many variations of the control room. It changes throughout the movie. The motion graphics are story driven. The design had to be readable and the information accurate; that was an amazing achievement. Was difficult from a scheduling point of view until you have designed what you put on the big screen, because its hard to get close to your setup in lighting. Originally, while the designs were still being developed, we knew that it was a soft light. Once we had those elements coming in, we applied them and changed the color or intensity. But at least the rig would be working. At the end it was okay because we were changing the motion graphics for story points or the timing, but the design was done so we had our base for lighting. Production designer Aurélien Predal and the DNEG motion graphics team, lead by Eliot Hobdell, did amazing work.”

The production went with Katana and RenderMan over Clarisse. “In feature animation we work at the sequence level,” explains Philippe Denis, VFX Supervisor, DNEG. “A few key shots are chosen where we establish the look and create the lighting rig. When those key shots are approved, we dispatch that to the full sequence. Katana allowed us to structure our work in such a way that was much easier to pass on the development of the lighting rig.”

It was critical that proper human anatomy serve as the basis for the character designs. “You can have a pushed shape or pose but it stills needs to be based on real anatomy because if you go off, you’re just going to look wrong,” notes Sharma. “DNEG understood real anatomy through their visual effects work, but then you have to translate this into a specific design language. Our characters have human features like nose, mouth, and ears, but their design is quite different from an actual human.”

With the release of its animated feature film debut, Ron’s Gone Wrong, DNEG Animation steps into the spotlight. This is not new endeavour for DNEG, as the division was established in 2014. But as is the case in animation, productions take time, often taking from two to five years. Then there was also the matter of having to establish the methodology and technology to integrate the workflow and pipeline with Locksmith Animation, an upstart company as well. Thankfully, DNEG’s visual effects expertise meant that not everything had to be built from scratch, though a fair amount did, as animation is not usually – though can be – reliant on recreating photorealism and obeying the laws of physics.

Ron and Barney were the first characters to be developed, with the lack of physicality assisting the animation for the malfunctioning B*Bot Ron. “Where Ron becomes quite successful is that we were able to achieve a lot more by doing a lot less on him,” observes Sharma, who created 70 different faces for Barney. “Before Barney we had rigs of Dad. But because we had to work on the face, Barney became the first human character that we had to do. Each character benefited a lot from what we learned from Barney and Ron, in particular the faces of Grandma and Dad.” Proper balance was needed between the simulations and animation in order to be realistic but also to maintain the desired silhouettes and poses. “On the human characters, simulations are being run on the clothing and hair,” Sharma continues. “We stayed away from simulations on Ron and the B*Bots, which made them much easier to control. On the human characters it was important to have the two departments working together. If you go with a clean pose with a big jacket, then you’re breaking the rig inside. To get directors J.P. Vine and Sarah Smith to approve shots we would show them what broken elements we had, and later on made sure to clean the body.” Sharma adds, “Making things simple is hard because you have to be quite accurate and to the point of what you’re trying to achieve and say, rather than moving all over the place for no reason.”

Another important aspect of the animation production process was the development of generic characters. According to Denis, “We had big crowds, especially with the kids and cafeteria. The way that we want to work in animation is deterministic rather than random. You want to make choices early on in the design phase. What I pitched to the production designer and art director at Locksmith Animation was to layer the options like faces, bodies, shirts, pants, and colors in Photoshop and while doing this create the generic characters. Then we can ingest the Photoshop files and build the characters in Houdini. What DNEG had on the visual effects side was more random because they’re used to doing crowds containing thousands of characters. We wanted to have more control as we don’t do the big size crowds. We had to modify the pipeline in order to do that.”