I had almost no experience with animation and John had a very intense audition process. For my try-out, I arrived at 9am and then worked at the video down-shooter until 6pm. I think John was busy, so they asked me to continue the next day, creating cut-out figures using watercolor-dyed translucent fabric and then animating them in little 5 second clips. At the end of the second day, I asked if I should come back again and they said yes. My mom finally suggested I specifically ask if they wanted to hire me. I did and they did!

I was responsible for keeping all the plates spinning on top of the sticks. John would see the dailies, but he wasn’t in the camera rooms like that. John got the ball rolling, but then he went off and did other things, and left us to do it. And he did have a frustrating tendency where you’d develop something and he’d go, “Yeah, that’s not it…that’s not it either.” Well what the fuck is it!? That drove me crazy at times. When he went away to direct A Christmas Without Snow, it wasn’t like, “Oh, he’s gone, what’ll we do?” It’s like: Now we can run faster. But we’re running on his track, and with a lance aiming at his target. It’s just when he’s standing around in the track, the horses get spooked.

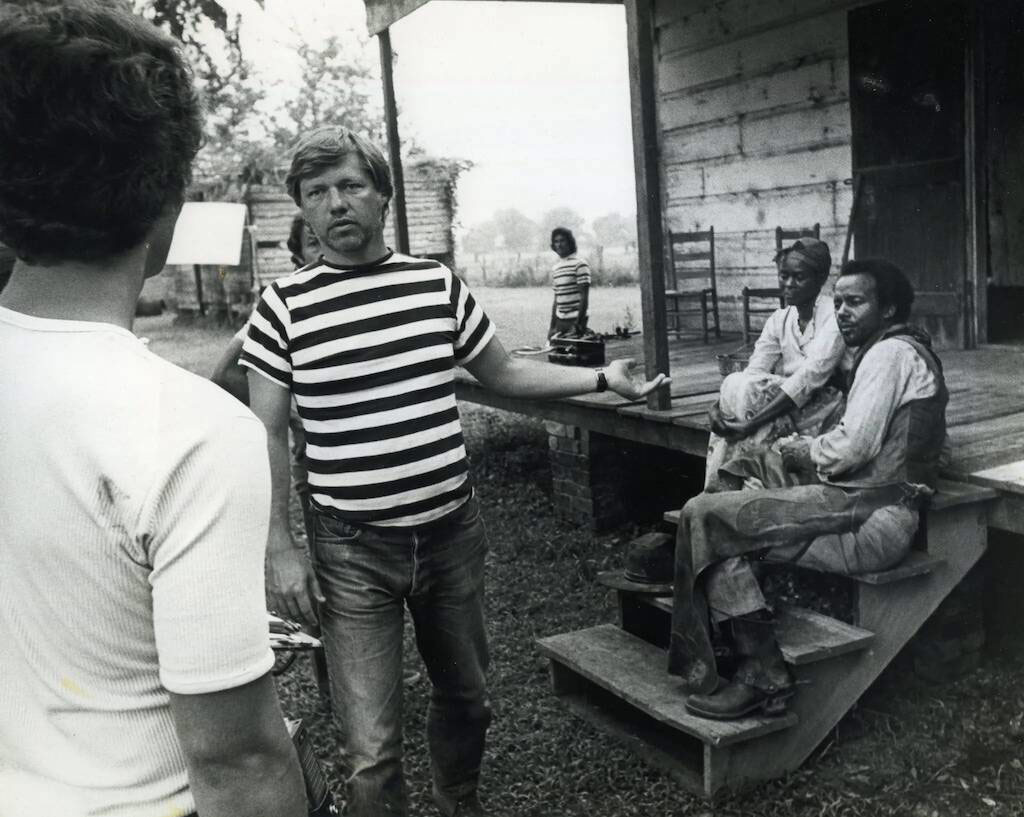

John really aimed to tell meaningful stories. He started out as a director of photography and he shot many of his features himself. Before [George] Lucas and [Francis Ford] Coppola, John pioneered the Bay Area filmmaking scene, showing that he could make great films outside of the studio system.

I called Korty Films, and he answered the phone. Coming out of Hollywood, I didn’t expect that. I talked to him briefly, and he had animation plans, but there wasn’t much going on, so I went back to San Diego, where I created the San Diego Chicken. I sent him one of those resumes, and they wrote me and said “Get back up here.” They wanted a gag writer for “Thelma Thumb,” their Sesame Street material. I started as a gag writer, and went to apprentice tabletop animator. I studied under Gary Gutierrez briefly before he left and started Colossal Pictures. When he left, I took over the Sesame Street operation. Then John went off to direct Oliver’s Story, and all of a sudden I was running the studio.

I was working as an animator at Disney. It was not the greatest of times. My old Calarts teacher Jules Engel contacted me and said there was a really cool project using cutout animation. I guess they’d come to him and other animation instructors looking for more talent to help.

Harley Jessup

John was a fantastic designer and his visual sensibility really resonated with me. The fact that he had won every award for his animation, documentaries, and live-action films is remarkable. Each project at Korty Films had a worthwhile and experimental quality — it felt like we were doing something new, but I loved that there seemed to be a bit of UPA in every frame. John attracted so many young artists and filmmakers to his little studio in Mill Valley. I was grateful to be one of them.

So I was running the show for a couple years on the Sesame Street side with this tight little crew. I wrote sixteen or seventeen of those, and Harley did all the artwork. It was a very skeletal crew. And then we launched into the feature, and holy get-out-of-the-way. We were zoned for seven employees and we wound up with fifty. There were trailers in the back. I was a supervising animator and a sequence director, but I shared the office with co-director Chuck Swenson. I had a walkie-talkie to call animators out of the trailer, but the thing didn’t work for shit, so I took some rope and tied a steel nut to it, and I’d open the window and throw it on the roof of the trailer. Then somebody would come out and I’d say, “I need Chuck Eyler up here right away!”, and I’d reel the nut back in.

John was very charming and a great storyteller. He had an appreciation for the spontaneity and improvisational quality of cut-out animation that was reflected in the fantastic improvised performances he got from the voice actors, many of whom John had recruited from The Committee comedy group in San Francisco. The cut-out animation was like a live performance under the camera, never completely in-control.

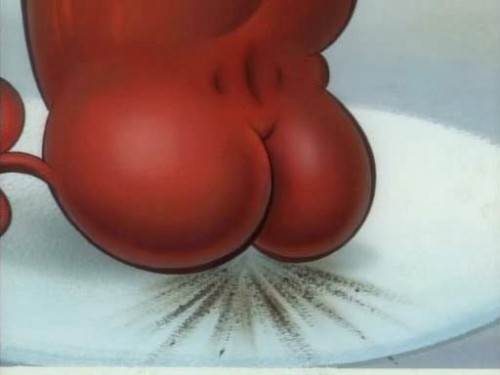

It was a huge change. I wasn’t well-paid at Disney, but this was for a lot less money — but the project itself looked so cool and beautiful that it was worth it. I wish I could say more about what John did for me personally, but it’s more about the film he set up and the people he brought together that had the impact. It was a bold idea for a film, and a bold technique that he’d developed going back to his Sesame Street films, using Pellon and backlighting it for this gorgeous look. He built his studio in this house and created the environment, and co-created the script and the look, but at a certain point he backed away. I just think he’d been on it long enough and he was antsy, wanted to do other things, so he became a part-time director.

At lunchtime John Van Vliet and I would take our lunch bags, get on our motorcycles, go up Cascade Creek on a hot day, take off our boots and socks and put our feet in the creek and eat sandwiches next to a babbling waterfall. Are you kidding me? Try that in Hollywood. And working for Korty was a launching pad. I was the one out on the road promoting the film, so I became part of the Star Wars roadshow. It was a three-hour presentation for Comic-Con, Worldcon, all these places we went.

Henry Selick

Korty was also a mentor to many talented artists, giving them their first break in the business and helping them develop their skills and expand their creative horizons. His recent obituary in The New York Times affirmed the commitment to social issues and interest in everyday characters and struggles that was present in all of Korty’s work, but while his live-action credits are certainly worth celebrating, Cartoon Brew sought out comment from some people who worked for and with him in the production of his groundbreaking animation work, and whose careers would not be what they are today without his help.

I got the job, and my wife and I moved up in fall 1981 and found a place to live. John had been involved on the film for a couple of years, but it had been in production at least six or eight months. I got to know John and see some of his independent live-action films, and I grew to know his animation. I had huge respect for him. I think Harley and John had the same design DNA. They had this amazing connection—what John wanted for the film, Harley wanted too, and had the ability to create it.

Working on Twice Upon a Time was like coming to heaven, but it was really fucking hard. They had so little space and so few camera rooms that basically, when you started a shot, you were expected to live there until you finished it. I’d been on shows where you put in crunch time, but in this case it was the norm almost from the front. But the sense of fun and creativity in the work was so high. We all stuck it out because we thought it was going to be great.

John Korty, creator of the “Thelma Thumb” series for Sesame Street and director of live-action films as well as the animated feature Twice Upon a Time, died on March 9 at the age of 85.

Harley Jessup, production designer on Twice Upon a Time, later came to Pixar and designed films including Monsters Inc., Ratatouille, and Coco. Henry Selick, a sequence director on Twice Upon a Time, went on to direct films including The Nightmare Before Christmas, James and the Giant Peach, Coraline, and the forthcoming Wendell and Wild. Brian Narelle, supervising animator on Twice Upon a Time and the “Thelma Thumb” series, is a writer, animator, character designer, and actor, and starred as Lt. Doolittle in John Carpenter’s feature Dark Star.

I went to George Lucas’ effects company in L.A. and met producer Bill Couturie, and I saw this gorgeous, unbelievable footage. It was mind-blowing — it was so much like the films that actually got me into animation. I didn’t get into animation to make Disney-type films; I got into it because of things like National Film Board of Canada shorts. I heard George Lucas was involved, and that it was shooting in Mill Valley, where I’d never been. It just seemed like it was worth taking a chance. They flew me up and had me do an animation test. They gave everybody a little kit of characters, and you’d flop them down and bring them to life. When I met John, he said I’d done the best test of anyone they’d ever tested, but he had reservations about Disney. (laughs) And I was probably the least Disney person at Disney. I’d always like experimental animation.

I had the first hour, Frank Marshall had the second hour with E.T., and Sid Ganis had the third hour with Return of the Jedi. Probably more people saw my presentation than ever saw the movie, because I had a captive audience. In Chicago there were 2,000 people. Talk about being spoiled. I was traveling with Sid Ganis and Howard Kazanjian and Kathleen Kennedy, and now she’s in charge of Lucasfilm. Those were tremendous opportunities and experiences.

Korty was born in Indiana and went to Antioch College in Ohio. He made his first animated film by bleaching the image off a Mickey Mouse cartoon, then hand-painting the frames. Korty relocated to California’s Marin County in the early 1960s and started making features. He already had an Oscar-nominated animated short, Breaking the Habit, and three independent features — The Crazy-Quilt, Funnyman, and Riverrun — under his belt when he met George Lucas in 1968, who immediately called his friend Francis Ford Coppola to suggest that moving to the Bay Area would be conducive to fulfilling their cinematic ambitions.

Brian Narelle

John got me out of L.A. I mean, look where we are — we’re in Mill Valley, California, one of the most beautiful places on Earth. I went from gag writer to apprentice animator to full animator to supervising animator to director, and it was like standing in one place and being promoted from Private First Class to Lieutenant Colonel while living in paradise. More things may or could happen in Hollywood because it’s Hollywood, and there’s more stuff going on. But you’re in L.A. dealing with all that crap. You’re not in a redwood goddamned forest.

John was very individualistic — there was a personal vision in everything he did. He brought to American animation a look and a vision that had never been brought to a feature film. And man, the people who worked there! It felt like, “This is why I got into animation.” And I don’t even feel that in my own work I’ve been able to have quite as strong a vision. You have to give a little to get a little, even though I’ve got my way to a certain extent. But with John, it was like, “No compromise! We’re going to make this movie.” I just wish he’d stuck around a little longer as a full-time director. I would have liked to be around him a bit more. He had a good life, and he had a big impact.

John inspired George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola to come up to the North Bay. That changed things in ways we can discuss forever. But in terms of my experience in and around Korty Films, he gave young people all kinds of chances, all kinds of opportunities, me among them. The Hollywood world just wouldn’t operate that way. You wouldn’t have this camaraderie in a three-story Victorian house with a trailer out back with some idiot throwing nuts at the roof. (laughs)

It was a tiny crew, and at one point we lost our art director — I didn’t know this — and I went upstairs and saw this guy who looked like a high school kid. I went back downstairs and said, “Where’s our art director?” “She left.” “Whaddya mean she left? Well who’s that kid upstairs?” “Oh, his name is Harley. John just hired him out of Stanford.” Stanford! I thought he got him out of middle school, the kid looked so young. This was the beginning of four or five years working with Harley Jessup. It doesn’t get any better than that.

Korty’s production company operated out of a three-story Victorian home in Mill Valley, and Korty would take on directing jobs for telefilms while simultaneously organizing his own animation studio to make short subjects for Sesame Street. He directed acclaimed films such as The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1974) and Farewell to Manzanar (1976), while his animation crew made the films in the “Thelma Thumb” series of two-minute shorts for Sesame Street.

He created an environment where he also was doing amazing documentaries, like Who Are The DeBolts, he was doing commercial tv stuff like Pittman, and he’s doing all this crazy animation, and inventing styles of animation and techniques that just haven’t been seen. There aren’t that many people with that kind of eclectic resume.

I was in San Francisco’s North Bay, and I didn’t know anybody, so I needed to make a resume. I hate resumes — a list of shit I don’t care about — so I did a nine-page comic book instead, “Resume Funnies.” My character Crawford Crow narrated it, and made up a lot of lies, but told a lot of truth. And I’d read about John Korty in Newsweek, probably because of Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, and apparently he did animation too.

I met John at the Stanford Design Conference. I had just graduated and he was looking for designers for his animated feature, Twice Upon a Time. I immediately veered away from graphic design into film design and never looked back.

The thing about John that made the biggest impression on me was the way he built a cart, put some people in it, and pushed it off a cliff. He set up the studio, he got all the people hired, he had the film in motion, and the vision, and the characters. Then he let people have a lot of room. John was more executive producing, or “executive directing.” As soon as Chuck Swenson was brought up from L.A., Chuck was cranking out storyboards and driving the ship, and I was over his shoulder scolding people. Chuck and I would go from camera room to camera room like good-cop-bad-cop. He’d go in and without even looking at what they were doing say, “Wow, you’re doing a great job! This is gonna be great!” And then I’d say “Yeah, but inch this up, and make sure there’s a consistency in where the head is in relation to that…” And we’d move on to the next room.

Working at Korty Films was heavily influential on me because it felt so freeing. I’d made lifelong friends at Disney, I learned a shit-ton about storytelling and filmmaking, but John represented the path I’d originally thought I’d be on, which turned out to be such a rare path in the animation industry. I interacted with John and had some meals with him and talked about film — I told him about what a genius this young guy Tim Burton was, and we actually got Tim to come up, not long after Frankenweenie, and John put him in a room and had him draw things and liked his work. And it might have been wise for me to move back to L.A., because that’s where most of the work was, but ultimately by moving away it led to other interesting projects, like the MTV work I did — and building a team of people, so that when I reconnected with Tim and he said he’d be making Nightmare Before Christmas, I already had a small group of people who could all step up and be supervisors on that show.

In the late 1970s Korty and company began pre-production and eventually production on an animated feature, Twice Upon a Time (1983), a gorgeous and hilarious family film unfortunately trapped in an era when children’s films were almost impossible to market. Animation Blast published a production history of the film in 2006 (download PDF HERE), which detailed the variety of circumstances, both internal and external, that doomed the film to be a financial failure that went virtually unseen by the public.