Victoria Davis is a full-time, freelance journalist and part-time Otaku with an affinity for all things anime. She’s reported on numerous stories from activist news to entertainment. Find more about her work at victoriadavisdepiction.com.

Already passionate about unique, female-led stories, Brownmoore got to work on her first personal project, which aims to address two main misconceptions about autism.

Brownmoore says she too had a very different view of autism before her son Oscar was diagnosed five years ago at the age of six.

She adds, “I felt very worried about showing my clients and people who I was working with, even in the future. At first, when I started, I thought about keeping it under wraps and just doing it completely myself, not involving anybody. And, when I started to realize that would be impossible, I had to take a leap of faith and just hope for the best that it was all going to be ok.”

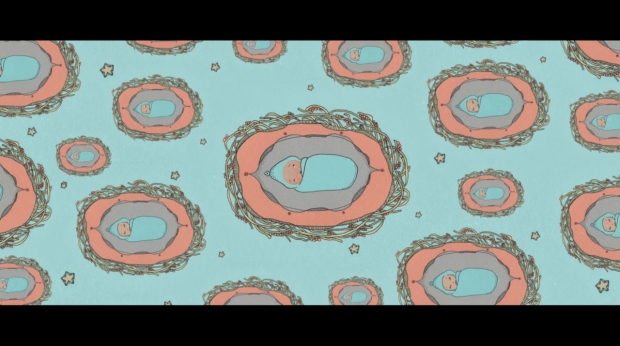

The hand-illustrated animation, co-produced by George Chignell and executive produced by Serena Armitage, is being released on Vimeo in honor of World Autism Day – April 2.

As the little girl whispers to the butterfly, the film shows the little critter flying off and landing on the forehead of a young baby, who also isn’t sleeping, just like the main character in the beginning of the story. The baby then closes their eyes and goes to sleep.

“Lots of people interpret this differently and I didn’t want to be didactic in the experiences to what was happening but, to me, when the butterfly rests on the baby’s forehead who can’t sleep while all the other babies are sleeping, it’s like he’s passing on this message that it’s going to be okay,” explains Brownmoore, who had to give herself that same reassurance on a regular basis throughout production.

“The first one was empathy,” says she says. “I think a lot of people just don’t realize that autistic people can be empathetic. There’s a moment in the film where this little girl is at a birthday party and one of the children’s balloons bursts. And the child starts crying. And all the other characters actually move away. But the little girl goes up and gives the child her balloon, which is something my son absolutely would do. He’s a real peacekeeper.”

“Since the film’s come out, my son and the film have both been used by some people now in the community to help people who are going through that tough diagnosis process,” Brownmoore shares. “I also think I’ve helped Oscar find his voice in this. We’ve had so much dialogue about it. When his diagnosis was revealed to him, which came a bit later, we had the film to talk about it. It became this great point of conversation for us. And he felt so much relief, able to use the film to talk about his autism because it was like all these dots connected for him.”

“That’s when I saw all this from a completely new angle and a new light,” notes Brownmoore. “I thought, ‘Oscar’s got this gift and he’s amazing. Why are we getting so hung up on this diagnosis when, actually, that’s not the most important thing?’”

“It was super scary, there’s no question,” she says. “I felt this pressure to represent Oscar in a way that is fair to him. I felt pressure from the autism community to represent them in a way that felt authentic to them as much as I could, coming from one person’s experience. And then also, professionally, I felt a lot of pressure. I’ve always worked on other people’s films. I’ve bought other people’s visions to life. And this was the first time that it’s been my vision.”

“A lot of autistic people find comfort in nature and animals, because nature doesn’t have that pressure of social expectation regarding how to communicate, react, or interact,” notes Brownmoore, whose film regularly features tiny animals looking to engage with the young girl character. “Everyone else turns away from the caterpillar in the school. But the main character engages with it. Also, at the end, she speaks to the caterpillar, which has now become a butterfly. And that’s the only being that she actually speaks to in the film.”

But what if this baby isn’t awake because they are different. What if it’s because they simply see the world differently? This is how director Allison Brownmoore begins her animated short film, The Amazing Adventures of Awesome, that tells a story of how beautiful and exciting the world can be as seen through the eyes of a young girl with autism.

Brownmoore hopes that, with the film now available for everyone to watch, it will spread a more positive light on autism for those who get a chance to see it. “I’d really love them to be enamored by this little girl’s world, and just feel the sense of joy and optimism and beauty in a world that has a character that sees things differently,” says Brownmoore, who adds that she has caught the bug to create more animations about characters on the autistic spectrum.

Then, Brownmoore says, she had an experience with Oscar at a music festival in England that kind of “changed everything,” and “was the impetus of the film.”

Brownmoore illustrated the film’s visuals herself – from the birthday parties and circus tents, to school story sessions and forest adventures – and then got animators Sylvain Doussa, Kevin Smy, Amalie Vilmar, Mairead Ryan, and Jamie Kendall to bring them to life in 2D. Using the After Effects plugin Duik for the animation and Flame for editing and finishing, The Amazing Adventures of Awesome has a contemporary picture book look, the story told almost entirely in light hues of red, blue, and green.

“One of the things Oscar really likes to do is high-five people randomly,” says Brownmoore. “So, we were walking around this festival and there was a narrow path through this forest and people were walking toward us from this big tent where a band had just finished playing. It’s quite late at night, everyone was somewhat downtrodden, looking a bit sad, and then Oscar just started high-fiving them and, because I was walking behind him, I could see the aftermath of the high fives. These people just came alive and they’re laughing and smiling and joking.”

“I knew that I didn’t want to go live-action, even if cost wasn’t a concern, just because, for the story, it was really important for it to feel like it had a magic element to it,” explains Brownmoore, known for her visual effects work on films like We Are X and Assassin’s Creed, as well as her design director work on documentaries like Nothing Compares and The Return of Tanya Tucker. “I really wanted it to be very beautiful and magical. I didn’t feel like we had many beautiful stories about autistic people.”

And it has, for both Brownmoore’s film, which was part of the official selection of 29 film festivals, as well as for her son Oscar, who is now 11 with plenty of questions of his own about autism.

“I’m really passionate about characters that are different, and telling stories that are different,” she says. “If we can find the beauty within that and not focus on the differences and the challenges of the differences quite so much, then my job would be done.”

If one baby lays awake in a nursery, while the others are asleep, this small and insignificant detail somehow makes them “different” compared to the others that are “normal.” Behavior conditioning starts early too, where, suddenly, it becomes the nurses’ mission to get this child to sleep like every other baby.

The “Steiner aesthetic” is also very present in Brownmoore’s film. Inspired by the principles created by Rudolf Steiner – the founding father of Anthroposophy, which is a belief in using natural ways (or nature) to attain optimal mental and physical well-being, as well as understanding the whole self – Brownmoore’s illustrations highlight the main character’s connection with the natural world around her, whether through high-fiving trees or being the only kid in the classroom not afraid of the caterpillar crawling across her textbook.

This scene with Oscar inspired one of the final scenes in the film, where the main character runs through a forest, high-fiving trees and making them blossom back to life.

“It was definitely quite a difficult time for us as a family,” she recalls. “He didn’t present with what we thought at the time autism was. He’s very empathetic. He’s very socially motivated. His behavior has always been very accommodating, and he always wants to do the right thing. So, it came as quite a surprise to us.”

Take a few minutes to watch this charming short:

While Brownmoore consulted with the autism community during the production – being sure she was representing not only the wide spectrum of autism correctly, but also representing autism in girls accurately – most of the story is a reflection of the magic she’s seen in her own son.

“Most of it is based on my experience with Oscar,” she confirms. “I think probably the biggest difference is that there’s a moment in the film where the little girl character says ‘No’ to these hands that come into the frame and push her to do something or be near these other kids, which represents a parent or a teacher trying to shape autistic people to fit into a neurotypical society, rather than let them be who they are. That wasn’t based on my experience with Oscar. He hasn’t done that. But I actually am hoping that he does. That’s why I put it in the film. I think it’s really important that he finds his sense of self. And I think we’re getting there.”

She continues, “The second thing that I really wanted to change was this idea that autism needed to be presented in a way where we need to empathize with the character, and that the character is so socially withdrawn that everything’s been difficult. I don’t want to take away from the complexities that are certainly there for some people. The journey is really difficult. But I also didn’t feel like we always needed to tell that story. I think that it is really important to show that autistic people can be joyful and they can be funny, and the struggle is not something that people need to automatically emphasize in that world.”

Even before early childhood, during infancy, society starts labeling kids as “different.”