The NVIDIA 3D MoMa rendering pipeline reconstructs the triangle mesh model — one of the most useful models for artists and engineers. This enables creators to easily edit a 3D representation of an object or scene in ways that no other technology previously made possible.

“These new objects, generated through inverse rendering, can be used as building blocks for a complex animated scene — showcased in the video’s finale as a virtual jazz band,” says Salian.

The white paper detailing NVIDIA 3D MoMa will be presented at CVPR tomorrow, June 22. at 1:30 p.m. Central time. It’s one of 38 papers with NVIDIA authors at the conference. For more information, visit NVIDIA’s website.

Within an hour, a single NVIDIA Tensor Core GPU can generate the three key features of the triangle mesh: a 3D mesh model, materials, and lighting. Using the mesh, developers can modify an object to suit their creative needs; 2D textured materials are laid over the 3D meshes like a skin; and an estimate of lighting needed for the scene allows creators to later adjust their lighting of objects.

Max Weinstein is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. He is the Editor-at-Large of ‘Dread Central’ and former Editorial Director of ‘MovieMaker.’ His work has been featured in ‘Cineaste,’ ‘Fangoria,’ ‘Playboy,’ ‘Vice,’ and ‘The Week.’

NVIDIA will present the paper behind 3D MoMa in New Orleans this week, during the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

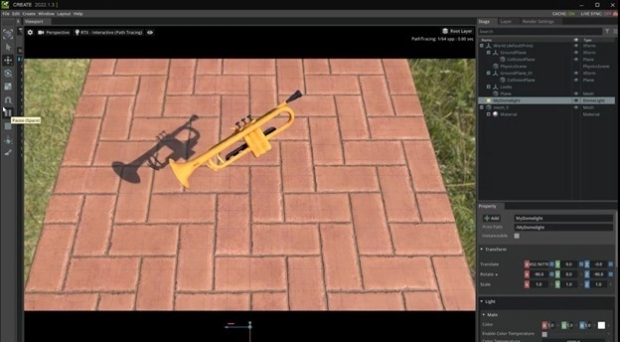

When editing the trumpet model, the team converted its original plastic to gold, marble, wood, and cork — demonstrating NVIDIA 3D MoMa’s ability to swap the material of a generated shape. (This process was done for each instrument, to reflect the team’s desired looks for the objects.) The team then placed the edited instruments into a Cornell box to test for rendering quality. Ultimately, the experiment proved that the virtual instruments would react to light in the same way that they would in the real world: brass reflected brightly, while matte drum skins absorbed light.

[embedded content]

Source: NVIDIA

According to NVIDIA’s Isha Salian, this method – called NVIDIA 3D MoMa – “could empower architects, designers, concept artists and game developers to quickly import an object into a graphics engine to start working with it, modifying scale, changing the material or experimenting with different lighting effects.”

NVIDIA 3D MoMa reconstructed these 2D images into 3D representations of each instrument, represented as meshes. The NVIDIA team then removed the instruments from their original scenes and imported them into the NVIDIA Omniverse 3D simulation platform to edit them.

David Luebke, vice president of graphics research at NVIDIA, says that 3D MoMa relies on the technique of inverse rendering to reconstruct multiple still photos into a 3D model of an object or scene.

In a video celebrating the birth of jazz, NVIDIA pays tribute to the art form’s improvisational essence, with AI research that may one day enable graphics creators to improvise with 3D objects.

“[Inverse rendering] has long been a holy grail unifying computer vision and computer graphics,” Luebke explains. “By formulating every piece of the inverse rendering problem as a GPU-accelerated differentiable component, the NVIDIA 3D MoMa rendering pipeline uses the machinery of modern AI and the raw computational horsepower of NVIDIA GPUs to quickly produce 3D objects that creators can import, edit and extend without limitation in existing tools.”