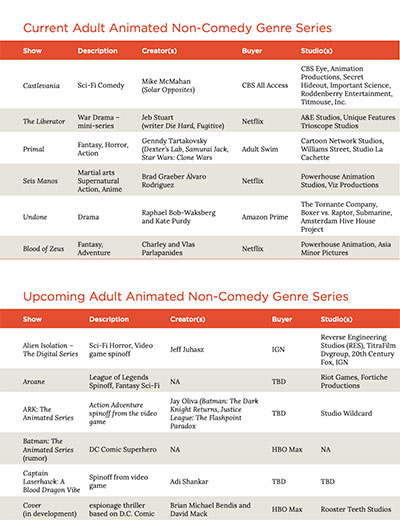

Naisbitt was best known for his work with the late Richard Williams, with whom he collaborated on everything from The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968) to Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). But his filmography ranged wider than that, taking in big-studio productions like Space Jam (1996), as well as acclaimed indie shorts such as Boyle’s The Last Belle (2011). To all his projects he brought his exceptional skills as a draftsman, and a talent for distorted perspectives and unconventional camera moves.

It was in live action that Naisbitt’s career took off. In the mid-1960s, he learned that Stanley Kubrick was shooting 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) in the outskirts of London and needed someone who could airbrush. Naisbitt joined the production and ended up working for two years on animation and visual effects with Douglas Trumbull.

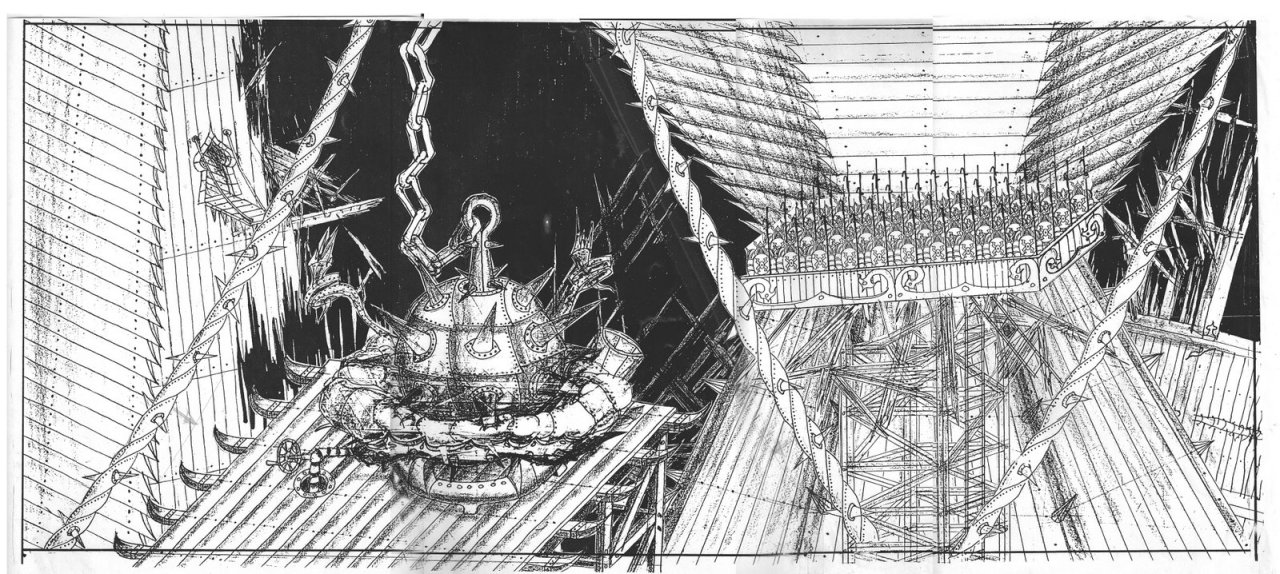

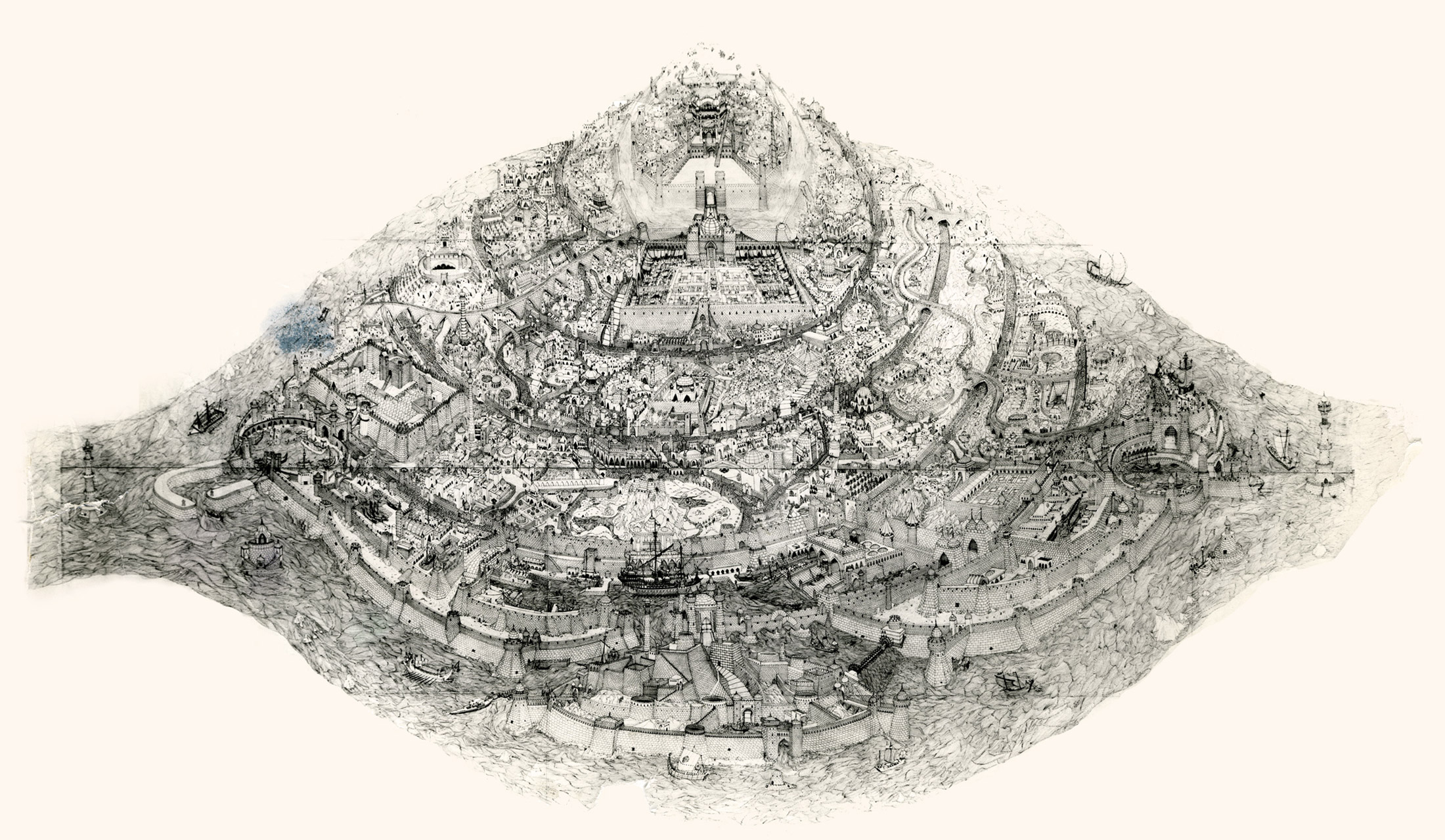

It finally dawned on me that one of the things that makes Roy’s work so unique is that he works the opposite way to many other layout artists. Rather than starting with a basic structure, a basic perspective grid, and building details up over it, Roy starts with a feeling, develops it in a kinetic way, and only afterwards tries to shoehorn the laws of perspective to it. The end result is something that appears solid and logical (Roy originally trained as a carpenter, so he understands structure brilliantly), but which is actually built upon the foundations of a dream.

After a stint overseeing the studio’s operational side, Naisbitt did layouts and backgrounds on Williams’s major projects, beginning with the Dickens adaptation A Christmas Carol (1971), which went on to win an Academy Award for best animated short. He later worked on the Maroon Cartoons film that opens the hybrid masterpiece Who Framed Roger Rabbit, another Oscar winner.

At the time, Williams was working in London on the animated segments for the live-action war epic The Charge of the Light Brigade. Hearing of Naisbitt’s talent as a technical animator, he hired him to animate a scene with a paddle-wheel ship engine. Naisbitt did the scene, after getting staff at a museum to show him how these engines work; Williams was pleased with the results and Naisbitt promptly joined his studio, Richard Williams Animation, in 1968.

But the greatest project in Naisbitt’s career, as in Williams’s, was The Thief and the Cobbler (1993), whose vastly ambitious production unfolded over more than two decades before being terminated by frustrated financiers. Naisbitt spent 12 years working on the layouts, handling “all the architectural stuff” and the virtuosic war machine sequence. His efforts earned him a credit as art director on the feature, which was released in various versions which Williams considered unfinished.

I met Naisbitt a couple of times. In November 2018 I saw him speak onstage at the British Film Institute alongside Williams and Boyle, after a screening of The Thief. I can confirm from experience what many others are saying: Naisbitt was as modest as he was talented. He spoke eloquently on his art, and gilded his comments with gently self-deprecating humor. He will be missed.

On stage @BFI yesterday with key colleagues Roy Naisbitt and @TheLastBelle Neil Boyle being interviewed by Justin Johnson. pic.twitter.com/d2UGloA4PA

In a blog post, Boyle described Naisbitt’s working habits in depth, writing in conclusion:

Parting ways with Williams, Naisbitt did layouts on Balto (1995) at Steven Spielberg’s short-lived Amblimation, which was staffed by many former Roger Rabbit artists. His last credit was on Space Jam — until Boyle, an animator on The Thief and Space Jam, tempted him out of retirement with a proposal to work on The Last Belle. Naisbitt created the bravura one-shot tunnel sequence — watch it below:

— Richard Williams (@RWAnimator) November 26, 2018