All in all, the book is an accessible whistle-stop overview of its subject. It will give invaluable insight to anyone wishing to learn more about animation from this anarchic, bustling, and often witty isle. If nothing else, it offers a tremendously strong foundation for future studies of individual creators and eras in the animation lineage of Britain.

Stewart has gone to tremendous effort to unravel the intricate events that made up the early years of animation production in Britain. This period saw the industry become a beacon of hope for avant-garde, experimental artists, British and foreign alike. British animation became well known for not only its willingness to experiment but also its embrace of international co-production. The industry welcomed artists from other countries, almost coming to rely on the talents and labors of people from Europe, Canada, the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, and elsewhere.

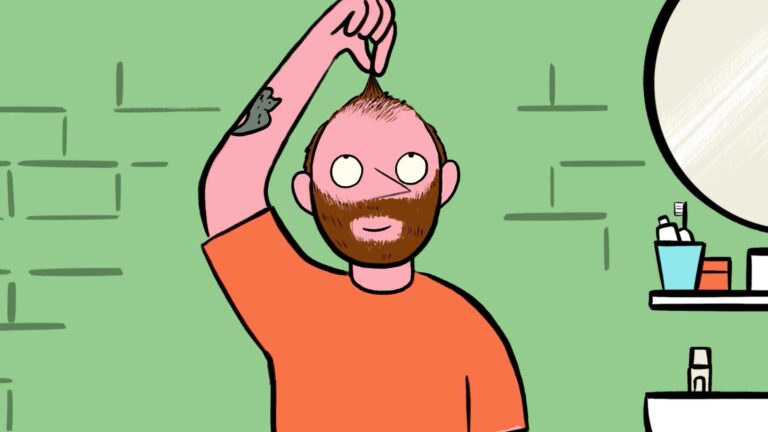

Image at top: “Creature Comforts”

The book is largely structured around a linear narrative of the highs and lows of British animation history, and how it relates to the global industry. Chapters focus on different points of importance. We learn about the heyday of children’s media content, with such superstars as Bob the Builder (1999–2011) and of course Peppa Pig (2004–), and about early innovation in computer animation, which allowed Britain to become a prominent player in the cgi/vfx market.

This period brought some of the country’s biggest, most profitable films and IPs to a global audience, yet at the same time a decline in financing and commissioning opportunities was damaging the industry at its roots. Young talent began looking outside the U.K. for funding and career opportunities. The country eventually faced the prospect of all its talent threatening to emigrate, until the introduction of a tax break in 2012 invigorated production as a whole.

In return, Britain offered these artists a space in which to freely try new forms of work and often make a home. This is strikingly at odds with the country’s current political situation under Brexit, which was not supported by those working in animation today.

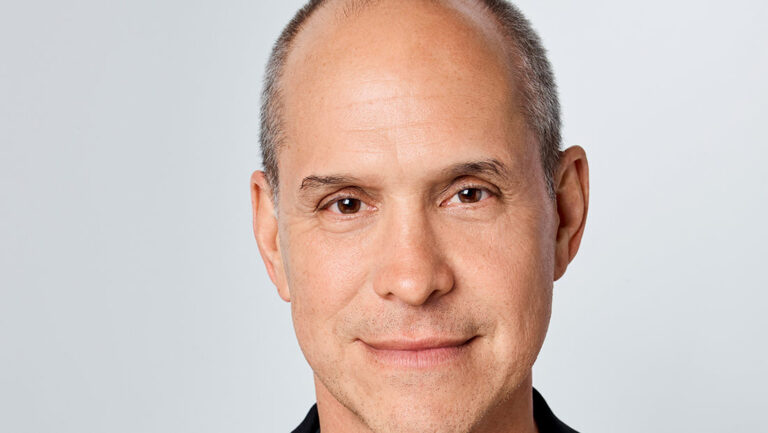

This relatively thin volume from Stewart, animation curator at the British Film Institute, covers the full history of British animation, from its inception to its current digital age. Some sections are understandably low on detail, with many of the more prominent and inspiring animators reduced to a passing mention; without prior knowledge, readers may have some difficulty recognizing these names, especially artists working in the contemporary era.

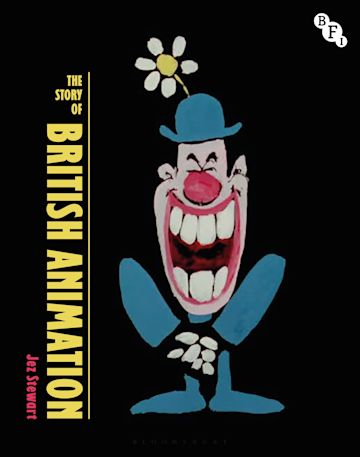

The Story of British Animation by Jez Stewart. Bloomsbury/British Film Institute.

It’s somewhat bizarre to think that this is the first book to fully contextualize the expansive history of British animation. Of course, others have written more specific books on various aspects or eras of British animation. Also, Britain’s story is far from lacking in the multiple volumes of world animation history.

This is nominally rectified by the inclusion of “close-ups”: focused mini-sections on people or areas of study that Stewart decided warrant further attention. This format too could be confusing for those wishing to read the book in full. But the issue is largely settled once you get used to Stewart’s fast pace.

In the final decades of the last century, the BBC, Channel 4, and Wales’s S4C used their (originally swollen, now diminished) commissioning budgets to promote new talents, develop new ways of producing animation, and set a new bar for quality of output that saw British animation through to the new millennium. Channel 4 in particular bankrolled an extraordinary run of shorts, some of which, like Nick Park’s Creature Comforts, won Oscars.