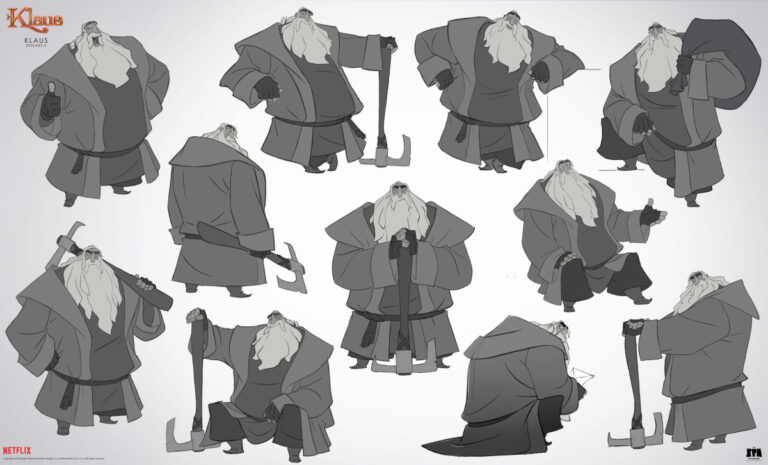

Alberto Mielgo: Everything in my films is either painted or a 3D render, and in fact The Windshield Wiper and The Witness are very traditional. It’s very much the old Disney technique, which is my favorite. It’s what they have been doing in 2D over decades, since Snow White, Bambi, until the last 2D films. In my case, it’s basically a 2D background with a 3D character on it.

In a Q & A conducted via email, Mielgo talked about his animation techniques, his aesthetic and thematic concerns, and the things that influenced his art.

My main goal here was to use the beauty of animation to depict something that is very mundane, something that can happen to you, to your next-door neighbor, rather than to fantasy heroes or whatever. So in a way it’s very risky, because obviously animation costs a lot of money and takes a lot of time, and it makes sense that animation producers try to be more commercial, in order to get something back economically. But The Windshield Wiper is very important as an exercise that shows how flexible the art of animation can be.

AM: My favorite thing about the film is that it’s completely independent – there were no executives or anyone else giving any sort of notes at all. And, second, it is very personal, it’s very much a take on love today, the way that I understand it, the way that I see it. I also love that the theme is definitely not commercial. It’s very simple, it’s basically so rich, and everybody can relate to the situations we represent in the film. It isn’t going to be a blockbuster, but the films that I like are never blockbusters. I like to have a small audience, rather than super-big hits.

AWN: Apart from having a similar visual style, the two films are very different in tone and structure. Where The Witness is hyperkinetic and has a mostly linear narrative, The Windshield Wiper is episodic and contemplative. Is there a reason you made this particular film at this time?

AM: I feel that if I start repeating the same formula over and over, I’ll be doing something wrong. The Witness is very much a chase and is very eclectic and very actiony. But it’s definitely not a fantasy world. The Windshield Wiper and The Witness could easily be taking place in the same universe. But the theme of The Windshield Wiper is very special, because animation nowadays is still mostly being used for fantasy or family-friendly films, or video games or other actiony kinds of things. It’s very rare to see animation used for themes that are much more simple and closer to humans – in this case, love.

So begins Alberto Mielgo’s new animated short film, The Windshield Wiper. There follows a series of vignettes – some disturing, some profound, some banal, all beautifully realized – that explore the nature of relationships and the many ways in which humans manifest what is arguably the most human impulse.

Usually I like to begin with a scouting period, in which I travel to a particular location. In the case of The Witness, I went to Hong Kong and spent about a week with a camera looking for my locations. Sometimes I do the storyboards before, sometimes I do them after the trip. Once I have my locations, photographs and references, I go ahead and paint them. In the case of The Windshield Wiper, I did all the paintings myself to make sure the 3D characters worked inside the paintings.

AM: The title is very important and very significant. Whenever we try to define love, we mostly fail, because it’s almost undefinable. That’s because the definition of love is based on relationships, and every relationship is different. I use the metaphor of a windshield wiper because every drop of water creates a pattern on a windshield, then the windshield wiper wipes the drops, and then the rain creates a completely different pattern. It’s never the same. Each pattern of drops is a different relationship. And this is also reflected in the rhythm of the film, which is the same as a windshield wiper. It shows and wipes and shows and wipes. It reveals a pattern, but the pattern is never explained. It’s sort of like a code that only the couples know, but really not even the couples understand the pattern.

AWN: Do you want to say anything about the meaning of the title?

AWN: Was any of the dialogue spontaneous or improvised, or was it all scripted?

AM: That’s a good question, and I love to talk about this. There are obviously parts of the film that were scripted, but for many scenes I did an experiment, where I explored male and female responses on the topic of love. Basically I organized two dinners with three males and three females and I asked them the same question. Surprisingly, or not surprisingly, their answers were completely different. It very much shows how males and females want very different things in love, which is why many times – or perhaps that’s just the main flavor in this film – love fails. In the film, you can actually hear a female talking about the urge to get pregnant or suddenly having to answer a call from nature, while the males are talking about wanting to have sex with a bunch of the females.

AWN: Both The Witness and The Windshield Wiper have a very striking style that seems to combine a number of modalities. Can you say a little about your techniques and your production process?

AWN: What was the biggest challenge in making the film?

AWN: What’s your favorite thing about the film?

Mielgo not only wrote and directed The Windshield Wiper, but served as editor, sound designer and composer for the film, which screened as part of the Directors’ Fortnight at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival. His previous animated short, The Witness, was included in Season 1 of the Netflix series Love, Death & Robots.

Inside a cafe, as others talk around him, a man smokes a cigarette and poses a question: “What is love?”

AM: I’ve given different answers to this question, but really the biggest challenge was not so much anything technical, but to keep the film alive for the six years it took to make it. This is an independent film that no one was putting any money into, so anytime I had another project, we had to stop working on it. After a year working on whatever gigs to pay the bills, you basically have to resurrect it, make it alive again. But it was cool because, as I was working on different projects, I was learning things that I would apply later to the film. So I was applying not only new artistic choices, but also new technical choices that I didn’t know about when I started. So, in a way, it’s an old film that had the advantage of being made over six years.

Jon Hofferman is a freelance writer and editor based in Los Angeles. He is also the creator of the Classical Composers Poster, an educational and decorative music timeline chart that makes a wonderful gift.