That’s the kind of thinking I was trying to do, where I could use different techniques, but still keep them familiar. For example, I used a lot of 3D printing for the mouth shapes and for different props. I found it very useful in speeding up the process. I could send something off to the printer and do something else while it was printing. It was this helping hand during the process. As I mentioned, I did hand-sculpted maquettes of the characters at the beginning, and then used that as reference for the modeling of those characters. I wanted to make sure that it still looked as though I could have made it by hand.

LP: It’s pretty close. There’s not a lot of new shots, but there are definitely tweaks in there, where I’ve gone in and changed some of the timing, especially through the process of filming live-action reference footage. That changed performance aspects, but not so much the narrative or the specific shots that were planned.

AWN: How much longer do you have to complete your degree, and what are your plans going forward?

LP: The lockdown aspect of it didn’t affect me too much because it was just me. In some sense, it forced me to commit to it and focus on it a lot more. I think the most difficult part of it was towards the end of production; when you’ve spent three years with this 10-minute film, it starts to do your head in a bit. You can lose perspective, and it’s very difficult to make decisions about things that you’ve seen a million times. I’m always conscious of that. That’s why when I’m storyboarding, and working on other pre-production stuff, I try to get as close as possible to what I want the final thing to be.

AWN: From a creative standpoint, what does stop-motion offer you as an artist, and why do you think audiences respond differently to it than other types of animation?

LP: I basically did everything myself and it took three years. There were two supervisors at the film school who I would meet up with regularly and go over what I’d done, and what I was planning to do, and they acted as a sounding board. Then I would go away and build the sets and the puppets and so on. It was in the midst of lockdowns. It was all very solitary.

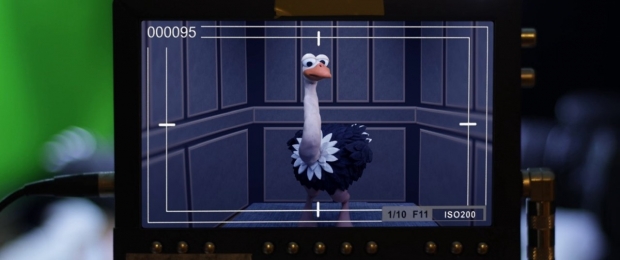

In An Ostrich Told Me the World Is Fake and I Think I Believe It, a young telemarketer is confronted by a mysterious talking ostrich, who informs him that the universe in which he lives is stop-motion animation. Understandably, he puts aside his dwindling toaster sales, and focuses on convincing his colleagues of his terrifying discovery. Quite meta of him.

AWN: Were you successful in that?

To understate it, Lachlan Pendragon’s road to an Oscar nomination was a little different from most filmmakers.’ As an undergraduate student at Griffith Film School in Brisbane, Australia, he discovered a love of stop-motion animation and, when it became clear that his best chance of making the film of his dreams involved enrolling in a doctoral research program, he went for it.

AWN: Was it always going to be an ostrich?

LP: It wasn’t always an ostrich. I wanted something that would be very out of place in an office environment, that would just bumble around and knock its head on stuff. I thought this big gangly bird was the right fit. It needed to be scary, but it couldn’t be too scary because of the twist that comes later. Earlier on, there was the idea of the main character’s lunch coming to life, or something like that, and speaking to him. There were lots of different things that I went through before I got to the ostrich character.

LP: There’s a history in animation of characters realizing that they’re in an animation, or the animator becoming part of the story. As an animator in stop-motion, you sometimes think while you’re animating, “Oh, I wonder what this character would think if they saw this environment.” It’d be a horrific thing. Their faces can come off, there’s a tray of their faces… It would be pretty horrific. You can see parallels with live-action films that sort of deal with that, like The Matrix and The Truman Show. I knew that there were going to be some dark existential themes, but I also wanted to make sure that there was some humor in there as well.

AWN: How long did it take you from writing the first words of the script to completion of the film? And how many people were involved?

AWN: You mentioned that you made this during lockdown. Did that present a significant challenge? Were there other things that were notably difficult?

AWN: Was it color 3D printing or did you have to paint the pieces?

“I wanted to make a stop-motion film and one of the ways I could do that, and also get some money for living expenses, was to go down the academic route,” he explains. “The degree is a doctorate of visual art.” That’s one way to fund your project.

LP: I don’t have the doctorate title yet, but it’s all pretty much done. It just needs to be moderated and go through that final process. As for what’s next, I’m really exploring those options because I did not expect to be in this position – making a student film and having it go this far. The dream for me is to get involved in feature animation. I love those films that have a really wonderful sense of humor and incredible design style. I hope to be involved in something like that down the track.

AWN: Were there any particular films or animators that you looked to for inspiration with regard to design or execution?

LP: I grew up watching [Aardman films] like Wallace & Gromit and Chicken Run. That was my childhood. I didn’t know that that’s what I was going to end up doing at that time. I feel a lot of nostalgia for those films. and I definitely draw a lot of inspiration from them. I definitely learned a bit about how to use more advanced techniques, but still retain a tactile quality. For example, there was this cool thing in Early Man, where they wanted it to look like plasticine, but they couldn’t because there’s a lot of hair and fur and stuff like that. So they made a plasticine mold and then recast that in silicon. It still looked like plasticine, but it functioned like silicon.

Dan Sarto is Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Animation World Network.

Prior to receiving its Oscar nod for Best Animated Short Film, Pendragon’s film screened at Annecy, Zagreb, and the Berlin Interfilm Festival, among others, and won a Student Academy Award and the award for Best Australian Short Film at the Melbourne International Film Festival. We spoke with the filmmaker about his unusual journey, his production process, and the deep reasons underlying his decision to feature a large, flightless bird (aka Struthio camelus) in his short.

LP: It’s a really great question, and I don’t know if I can fully answer it. But it’s such a simple concept for people to understand – that these are real objects and they’re being brought to life in this way. There’s something very open about it; you’re not trying to trick them into some kind of immersion and it’s very obvious how the effects are achieved. Because of that, your audience is more willing to jump on board and suspend disbelief, even though it’s so clear that these are craft materials essentially.

The ostrich came after that.

Lachlan Pendragon: I began by scripting the story, and then I sculpted a maquette of the main character to give me a sense of what they would look like. That helped me continue to write and improve the characters and the dialogue. I went from that to the storyboards and the animatic. I modeled all the basic geometry of the sets in Maya to make sure that it could fit, to see how big things were going to be, what camera angles I would want to use. Then I went and just shot a lot of reference footage. At that stage, I saw it as a nine-minute film. After shooting the reference footage and thinking more about the nonverbal performance aspects, it grew to be an 11-minute film.

LP: They were hand painted. Obviously they have the capacity to print in color, but for a home production – you can do a lot of cool stuff and it’s getting better all the time – but not quite full-color 3D yet.

AWN: Let’s begin by talking a little about your production process. How did you start and what steps did you take prior to actually shooting?

AWN: How did you come up with the story?