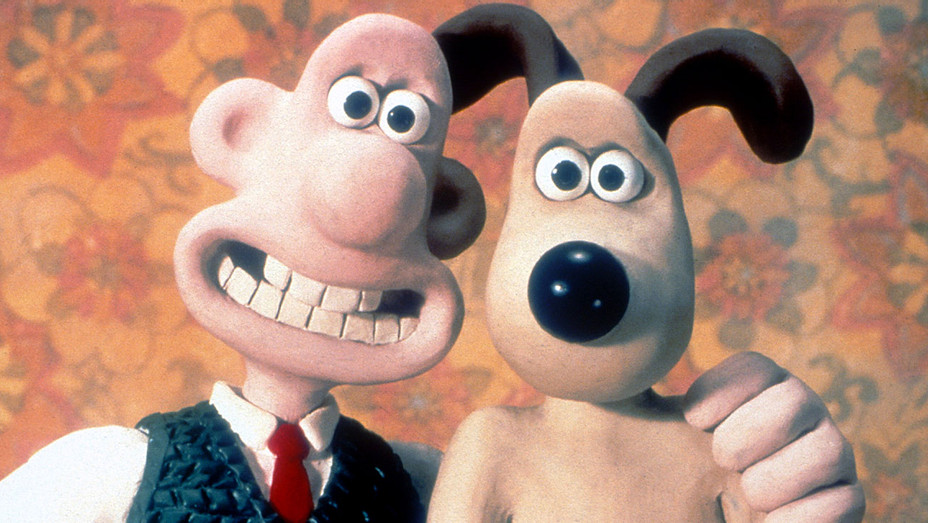

Song of the Sea is just the tip of the iceberg: the channel’s catalog is a taster menu of quality global animation. The Oscar-nominated stop-motion feature My Life as a Zucchini is there, as is the Studio Ghibli co-production Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter. Peppa Pig vies for attention with Moominvalley and the delightful Chilean series Paper Port. Wallace & Gromit make an appearance, too.

Cartoon Saloon is a special case. The studio’s first two films, The Secret of Kells (which BBC Alba has also dubbed) and Song of the Sea, draw heavily on Irish mythology, which shares cultural roots with Scotland’s Gaelic community. As Cameron put it: “We share those stories with Ireland … so it was absolutely sensible for us to acquire that and dub it. Even the songs work particularly well in our language.”

These dubs remind us that, even once a work of animation has been released, its production can be extended through dubbing, its audience expanded, its purpose subtly reconfigured. The creators of the animation titles licensed by BBC Alba can hardly have anticipated that their film or series one day might play a role in strengthening a small linguistic community in Scotland. But here those works are, thrilling and beguiling the children on whom the future of Gaelic depends.

Last week, courtesy of the BBC, I rewatched Cartoon Saloon’s much-loved 2014 feature Oran na Mara. I’d seen the film before and enjoyed its elegant spin on Celtic folklore — but as I watched it now, I didn’t understand a word that was being said.

BBC Alba occasionally co-finances original animation: a recent example is the short film Sol, produced at Paper Owl Films in Northern Ireland. But budgetary limitations place a cap on these ventures. Similarly, rights to Hollywood titles are broadly inaccessible: “Sometimes it’s difficult for small channels like us to get within sniffing distance of a Disney catalog,” says Cameron.

U.K. viewers can explore BBC Alba’s catalog on Iplayer.

As well as going out on linear tv and the BBC’s U.K.-wide Iplayer streaming platform, the dubs are sometimes shown in cinemas and at cultural events. “That in itself is also hugely important for normalizing any language that’s not the main language of a country,” says Cameron. “You need to be seen in all the usual places. It’s important that you can go to the cinema … and see something in your own language.”

Once widespread across Scotland, the Gaelic community was slowly eroded by centuries of suppression and, more recently, the political and economic dominance of English. Today, some 60,000 people can speak it, although a study last year found that only 11,000 people do so habitually, most of them living on the country’s west coast and in the Western Isles. Unesco has classed the language as “definitely endangered.”

Since the 1970s, concerted campaigning has helped to shore up Gaelic’s place in Scottish society through various cultural and political initiatives. Animation started to be dubbed in 1992, when a fund was launched to finance tv productions in the language. In 2008, the BBC partnered with public body MG Alba, which has a remit to make and distribute Gaelic media, to launch BBC Alba.

Oran na Mara is in fact the film Song of the Sea dubbed into Scottish Gaelic, a little-spoken Celtic language indigenous to Scotland. The dub is one product of a remarkable drive at BBC Alba, the public broadcaster’s Gaelic service. For years, the channel has been licensing and localizing beloved animated titles as part of an effort to keep the language alive.

Cameron sees broadcasting and education as “two sides of the same coin in terms of language renewal and regeneration.” Some Scottish schoolchildren receive their entire education in Gaelic while a larger number study it as a standalone module, resulting in varying levels of facility with the language. Media like animation then complements that education. BBC Alba tends to license titles with relatively simple language, so that the dubs can be more or less understood by all kids learning Gaelic.

That explains the prevalence of indie animation on the channel. Cameron and her colleagues find titles at markets — chiefly Mipcom and Mipjunior — and through longstanding ties with certain distributors, not to mention the BBC itself. Their programming is guided by “good old public-service values”: Cameron tends to steer clear of anime or anything with a certain amount of violence.

It’s no coincidence that those titles are all family-friendly: the channel’s kids’ programming blocks, CBeebies Alba and CBBC Alba, are their main destination. “We haven’t really got the slots for adult animation,” says Margaret Cameron, one of the two commissioning editors responsible for animation at the channel.