The student’s voice is central to the program’s success. “We try to have as little influence as possible,” adds Subotnick. “We do try to encourage experimentation and the idea that each one of them has a unique voice.” Subotnick believes the freshman foundation is a key part of this process. “It’s a rigorous program, an art boot camp for their minds. It makes them think about what they can do in new ways. They arrive with an idea about themselves, and by the end of the first year they’ve given that up and opened their mind to all sorts of possibilities.”

Because of this foundation year, students apply to RISD, not to FAV. They submit a portfolio of their own self-chosen work, essays, and visual solutions to assignments that vary each year.

Risks at RISD

Emphasizing concept over technique, many RISD films end up with a lo-fi feel. They are intimate, flawed, explorative, and engaging. Even the missteps are frequently more interesting than some of the highest quality films from other animation schools. While it’s misleading to lump RISD films into cookie-cutter categories, dark absurdist comedies and freewheeling experimentation are common.

Where RISD Animation differs from other animation schools is through its encouragement of multidisciplinary study and the mandatory freshman foundation year. “No matter what you’re studying, everyone starts with the freshman foundation year, all doing the same drawing and design courses,” says Subotnick. “You don’t enter a department until the second year. You’re obligated to take whoever wants to come into the department. The students choose.”

The RISD undergraduate program lasts four years. “There are graduate programs,” says Kravitz, “but not for animation. So a student studying animation at RISD will have the first foundation year and then spend three years in the FAV department. Students from all across the university, however, take animation classes, sometimes even the animation thesis class.”

Around 1980, Andersen invited Kravitz to teach a class, and she remains an integral part of RISD animation to this day. Kravitz had been a filmmaker since the age of 11. “I was in a summer program in Newton, MA. Yvonne was teaching that program. I loved it so much that I started taking classes at Yellow Ball Workshop [an animation workshop for children co-created by Andersen], which was in Lexington, Massachusetts. I started assisting in classes when I was 14 at both places.”

Each film has its own unique and genuine identity. In some cases, it’s an attempt to locate that identity or voice and let it out, to let the world know: hey, this is me (or some fragment of me), warts and all.

“RISD also has liberal arts requirements,” says Kravitz. “The admissions committee does look at high-school grade point averages. The admissions committee is formed not only by admissions officers, but also by varying faculty members from across the college. The committee looks at many things in addition to, and more important than, technical skills [such as] original, creative approaches to problems, risk-taking, curiosity, genuine energetic interests, and thoughtful and original visual development. Simply put, the committee looks for unique voices.”

Building a program

Andersen was, without doubt, the main architect of the RISD animation program. As Kravitz, Steve Subotnick, and Agnieska Woznicka wrote in a 2016 article for the Melbourne Animation Festival, “Adept at finding simple solutions to complex problems, she believed in academic decisions by democratic rule, and she always did whatever needed to be done — whether that was cleaning up trash, repairing a camera, or writing reports. She was able to harness the creative and divergent energies of the FAV faculty into a powerful department.”

Overall, what separates RISD films from many animation schools is a sense of playfulness and curiosity, an almost naive willingness to explore and experiment with styles, tones, techniques. Yet it never feels like RISD students are adopting techniques and tones just for the hell of it.

This is a logical approach that too few schools seem brave enough to embrace. For many students, this might be their only opportunity to create their work unhindered by outside pressures. Education ain’t cheap, so artists are encouraged to let out what is already inside them, rather than waste time trying to impress someone else?

The roots of the animation program were planted in the early 1970s. The first animated films were made by students from other departments, including Candy Kugel and Karen Aqua. The program didn’t formally launch until the late 1970s, when Yvonne Andersen began teaching animation classes.

Initially led by Yvonne Andersen and now by Amy Kravitz, the acclaimed animation program produces films that are consistently thoughtful, eclectic, and technically adventurous, eschewing temporary trends and mainstream whims. Elective courses have been added over time and students can study character animation, character design, cgi, digital compositing, lighting, directing, sound for the screen, and more. The school also has a well-developed puppet-animation program.

The RISD animation program is part of the Film/Animation/Video department (FAV), which is under the school’s Fine Arts umbrella. FAV currently has seven full-time teachers and about 21 part-time instructors who teach anywhere from one to four courses. The department has approximately 130 students enrolled across all three years.

A deep artistic vocabulary

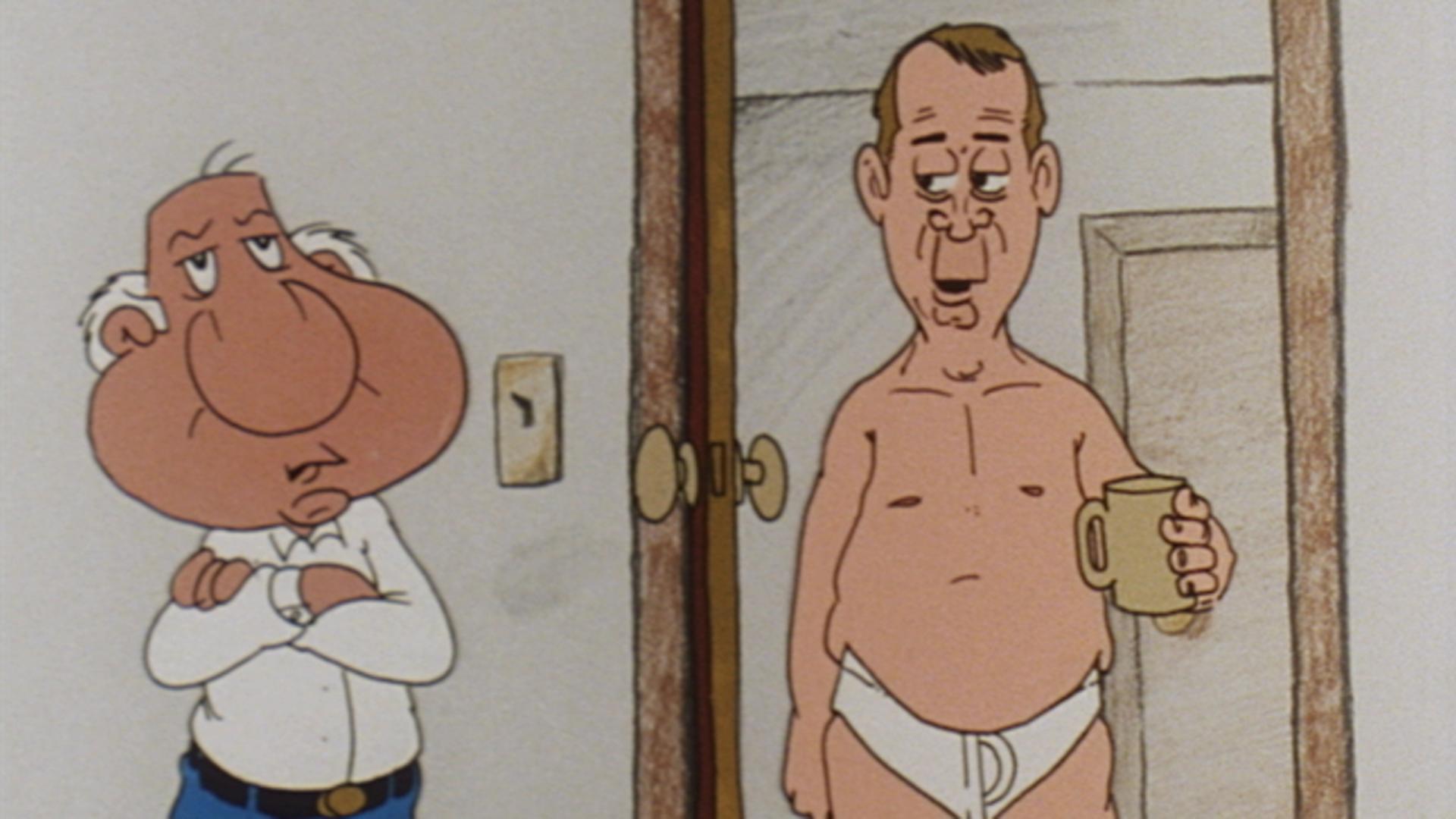

Pictured at top: “Mr. Smile”

The road towards a more absurdist tone arguably started in the late 1990s. Films like Space War (Christy Karacas, 1997), Mr. Smile (Fran Krause, 1999), Sub! (Jesse Schmal, 2000), and Red Things (Max Porter, 2003) were well received at festivals. They influenced future RISD films such as Violet (Ryan Ines, 2015), Talking Cure (Felipe Di Poi, 2016), Toto’s Tusks (Mehr Chatterjee, 2015), The Great Divide (Brent Sievers, 2014), Masashi Yamamoto’s films, and arguably the greatest tragicomedy of them all, Lesley the Pony Has an A+ Day! (Christian Larave, 2014).

Comedy aside, RISD has consistently created imaginative work that leans toward non-linear narratives and abstraction. On the Weave of Construction (Greg Buyalos, 1993), Made in the Shade (Takeshi Murata, 1997), Edgeways (Sandra Gibson, 1999), 12 Ball (Ara Peterson, 1997), Little Wild (Caleb Wood, 2010), Ripple (Conor Griffith, 2015), Toro (Lynn Kim, 2014), Doxology (Michael Langan, 2007), and Endless Forms Most Beautiful (Meredith Binnette, 2020) all demonstrate a long-standing willingness to encourage students takes risks with their work.

Once in the animation program, students are required to study live-action filmmaking, video making, and animation. “When students explore animation they have a deep artistic vocabulary with which to work — their thinking is not insular,” Kravitz explains. “Animation itself is a relatively small set of courses. However, students bring inventive, energetic thinking and rich skillsets to it, thereby achieving excellent results. The classroom is an active laboratory and failure is seen as a necessary element of a successful journey.”

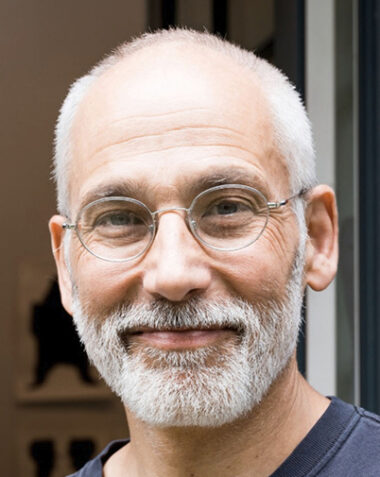

The third part of RISD’s animation leadership triumvirate arrived in the late 1980s. Acclaimed animator Steve Subotnick met (and later married) Kravitz while studying at Calarts. Later, he started teaching at RISD. “I started as an administrator running their computers,” says Subotnick. “Then I started teaching part-time at RISD and the [School of the Museum of Fine Arts] in Boston.”

The Rhode Island School of Design’s (RISD) track record in animation stands out for its success, longevity, and range. RISD Animation has given us the creators of Superjail! (Christy Karacas), Avatar: The Last Airbender (Michael Dante DiMartino and RISD illustration major Bryan Konietzko), and some animated series called Family Guy (Seth MacFarlane).

“The number of seniors who have specifically chosen the animation degree project class — basically a thesis class — is 22,” Amy Kravitz, an award-winning animation filmmaker, tells Cartoon Brew. But she says the number can be a bit misleading, as “some students are making animated installations and non-screen-based animation work in the Open Media — basically Video — area of our department, working between animation teachers and teachers from other areas of our program.”